Appreciating faiths: Lecture values Italy’s Jewish legacy

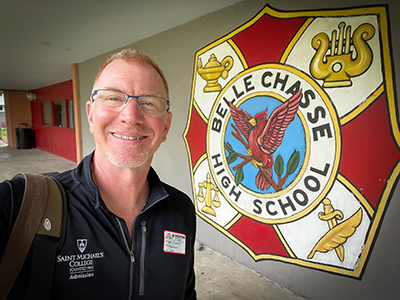

William Tortolano, emeritus humanities professor, chorale director and organist, began his Saint Michael’s faculty career in the early 1960s. It was just about the time when his friend, the wise and estimable Burlington-area Rabbi Max Wall, inspired what became a decades-long focused attention at the College toward better understanding and appreciation of Judaism — through a major ongoing lecture series and other avenues including the library’s enhanced Judaica collection.

On Tuesday, November 29, as part of the Faculty Colloquium Series in the Humanities, Tortolano advanced his late rabbi-friend’s important legacy with a well-attended noontime presentation in the St. Edmund’s Hall Farrell Room about the rich and vibrant history of Italy’s relatively small Jewish community, as demonstrated through art, food, architecture and stories of persevering humanity.

Tortolano, a sharp, cultured and energetic octogenarian, tapped his extensive personal travels, studies and wry humor to animate a talk accompanied by a slide show that featured many beautiful synagogues and other images of art, texts, musical notations, photos of food and scenery. President Jack Neuhauser, President Emeritus Paul Reiss and his wife, Rosemary Reiss, were among those attending alongside faculty, students and staff. Laurence Clerfeuille of the Modern Languages/French faculty (and also the lecture series organizer) introduced the program.

Tortolano explained that his interest in Italian Jews dated to his childhood growing up in an Italian neighborhood of Providence, RI, where his friend’s mother was an Italian Jew. That surprised young Tortolano since his own family and everyone else he knew was Catholic. Curious to know more, Tortolano asked his mother about it, beginning a lifetime interest that now is expressed in his collection of more than 50 books on Jewish topics. His mother explained that most of Italy’s modern Jews lived in the larger cities, along with vestiges of Italian Jewish communities from the middle ages in Southern Italy.

Later, he learned that the first Jews came to the region as Roman slaves in about the year 150 BCE, but soon became an important part of the community based on the admiration that Caesar had for their cosmopolitan knowledge the world, languages and commerce. “Problems came when Christianity became the official religion,” Tortolano said, “and from then on were terrible persecutions of Jews all over the world, particularly in Italy.”

His slides dramatized the sheer beauty of Italy’s synagogues, many still the spiritual heart for very vibrant congregations that are still going strong in “small but extremely vital communities.” He describe old dialects he has heard as a fluent Italian speaker in Jewish sections of such cities as Rome, Turin, Mantua or Venice. It was Venice where the Italian term “ghetto” came, originally meaning “foundry” for the largely Jewish section where cannon were made, he said.

The speaker had stories linked to various synagogues of which he had slides, revealing different historical episodes in Italian-Jewish history, many tragic: Nazis used Rome’s grand major temple as a garage for vehicles during World War II, though now it is a museum. He recounted how two Catholic janitors saved many sacred articles there, risking their lives, in those times. It was built in the mid-1800s, after Napoleon gave Jews their freedom, he said. Restorations of these Italian synagogues today are paid for by the Italian government, but it goes slow, he said. Italians generally had warmer relations with their Jewish neighbors in the century before World War II, even among Italian soldiers as the war started, but once Nazi forces moved in, the worst horrors began with deportations, mass killings and the desecration of holy sites. The main people to risk their lives in saving mainly children from the Nazis were Italian peasants, he said, since like their Jewish neighbors, they made children such an absolute high priority culturally, he said.

The speaker said that both Sephardic and Ashkenazi as well as Libyan Jews are found in many Italian congregations and communities, and this influences both worship and cultural things such as styles of food.

Did you know?

Tortolano’s presentation was peppered with interesting bits of information – for instance: the plausible possibility that Christopher Columbus was an Italian Jew, based on what we know of his navigation equipment and his own writings; or how names of Italians indicate where they came from in Italy, such as Romano from Rome or Veneziano from Venice, and many so-named families are quite possibly Jewish; also, that the only Italian Jew he has met in Vermont was originally from Genoa, lived in Montpelier, and he met her during a talk at the library there by chance. It appears the first Italian in Vermont was Joshua Montefiore (1762-1843) – who was Jewish, he said; Montefiore was an Oxford-trained onetime British lawyer, journalist and soldier who lived 10 years in St. Albans in the early 1800s, in part on a mission to propagate the British point of view in the War of 1812; he died poor, and was reburied by his descendants in the Hebrew cemetery in Burlington. Tortolano said he had met people who knew that man’s grandchild, a local doctor, and that man’s nephew was the prominent Moses Montefiore (1784-1885) in England who lived to 100 and gave a fortune to Jewish settlements in Palestine. His stunning estate (Tortolano showed slides) was torn down and is now a parking lot, sadly.

Tortolano spoke glowingly of wonderful Italian Jewish food and hospitality he has sampled on many visits with his wife and children to Italy, including tasty honey-and-walnut biscuits. One slide showed a beautiful medical diploma from the middle ages for a Jewish medical school graduate, since so many Italian Jews became doctors. He also showed music from Salamon Rossi, an Italian Jew who composed in the style of Palestrina. One slide showed a prominent Italian rabbi who was a friend of Pope John Paul, who called Jews “our brothers and sisters” – though, as the speaker reminded, “It took 2,000 years for someone to do that.”

All told, Tortolano said, “it’s a fascinating story that grows on you. They survived all those years. You wonder how they did it.”