Jay Rosen addresses journalism’s changing landscape

Watch recording of Jay Rosen’s full presentation at Saint Michael’s College>>

Jay Rosen, a prominent activist scholar and proponent of “public and civic journalism” in the service of more robust democracy, told a large Saint Michael’s College audience Wednesday evening that the U.S. has entered a “civic emergency” in the early weeks of the Trump Administration.

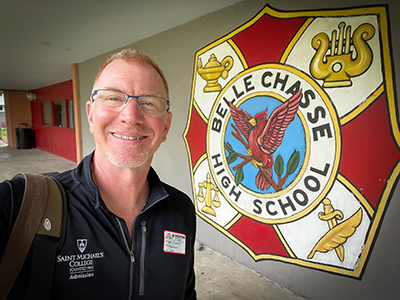

“The problem is not only how to cover Trump. It’s how to recover conditions in which responsible acts of journalism can make a difference,” said Rosen, speaking before a packed house in McCarthy Arts Center Recital Hall at the invitation of his former student at New York University, David Mindich of the Saint Michael’s media studies, journalism and digital arts faculty.

Journalists can and should take steps to rebuild trust with the public as part of addressing that emergency, Rosen suggested, given that many in the media had a lamentable role in these disturbing developments, even if the administration is the center of the storm.

Yet, he admitted to having limited answers in the wake of a sudden and overwhelming inundation of aberrations to our democratic conventions from President Trump and his inner circle in recent weeks that have included open hostility and demonizing of the press, the spreading of strategic deliberate falsehoods and the promotion of “radical uncertainty” (characteristic of rising authoritarian governments through history), an encouragement of polarization among Americans, and Trump’s demonstrated desire and ability to become essentially an independent media company unto himself, aimed at replacing the traditional press in reporting on his government.

Rosen suggested that big game changers of recent decades in White-House-press relations have been the rise of social media and a cable news ethos that is too often driven by politically affiliated “experts” and entertainment priorities more than in-depth reporting. Mainstream journalists’ clearly demonstrated inability to predict the Trump victory in the November election was humiliating to them, Rosen said, as it should have been, and surely eroded the level of public trust that might have existed before that.

In an introduction, Mindich said Rosen was a founder of the field of public and civic journalism in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as he become concerned about the decline in democracy and the public’s ability to affect change. He also plays a role as public “sense-maker,” and wrote the book What Are Journalists For? And for the past decade has been head of PressThink, a long-form blog on journalism, and has 90,000 twitter followers. He promotes open and respectful dialogue, Mindich said, which has become an ever rarer and appreciated commodity.

Some of Rosen’s key points in his main talk: Trump is using the power of the presidency to spread falsehoods, to turn “true” and “false” into “collapsed categories”; the new president “feels entitled to make stuff up” while “ “trying to make true and false kind of irrelevant”; also, that “lying leads to calling out lies” which leads to polarization, which helps Trump “by repelling those who are uncommitted.” He explained that recently it’s been all about a battle for a “middle group” of citizens – those neither all-in committed to Trump, nor all-in opposed to him, since those extreme groups are not likely to change, he said. “What’s new is a combination of a president who can speak directly to voters while trying to project hate at the press and discredit them,” Rosen said.

How to restore trust in the press? Rosen had a few suggestions: Reporters and news agencies must be up-front and clear about where they are coming from and lay out current priorities, then be able to say to news consumers, “We’ve done the reporting and this is what we found – what did we miss? We’re listening.” Because the old model has passed of the press speaking as “voice of God” without “showing their work” in the manner of school math proofs or scientific research, which should be more the model now. Rosen also said he thinks jokes in good humor rather than deadly seriousness will help build trust. The press, he said, “should be public, in-motion, revisable and adjusting to what’s happening in the world.” Some reporters have begun doing this with success he said, offering examples.

During a long question session, Rosen told a questioner about how to “make” other citizens better understand a particular point of view that “I don’t think you can make people do anything.”

“Start by listening to what’s troubling Americans, what bothers them, what they are anxious about in their daily lives” as a beginning to engaging them, he advised the press. Then, if news coverage reflects the things citizens are worried about, “people may start paying attention to you, and you can then address what Donald Trump is doing about it,” in a straightforward and matter-of-fact way.

“When you have a president violating democratic norms left and right, spouting falsehoods constantly, [a president] who doesn’t seem to have respect for our government and how it is supposed to work — it’s too much news, which is itself a tactic of control, whether or not it is deliberate,” he said in response to another question.

With the rise of social media, meaning no gatekeepers or authority or rules beyond algorithms, “lots of things that are poisonous to democracy can be distributed, and people participate in that. So it’s adding to confusion … It allows people to assemble their own information and become mini-broadcasters,” he said. The participation is good, but the poison, not so much, he seemed to be saying.

An audience member asked how to determine what news sources are trustworthy for consumers. Rosen responded that a good idea is having reporters pay attention to the extreme left and right and see emerging theories and hypotheses, and bring them together — The Washington Post has made that the beat of one reporter, he said approvingly. Also good indicators of trustworthiness are reporters who tell who their sources are, who can paraphrase the view they don’t’ hold and yet describe it accurately – “that’s the best clue to trustworthy that I know,” he said. Further, those willing to listen to criticism or engage in dialogue instead of “speaking from the mountaintop” might be more trustworthy. “And tell where you’re coming from,” he exhorted journalists. “Everyone has a mental picture of the world, and if you’re willing to share it, to me, that’s more trustworthy.” Also, readers ought to pay more attention to bylines and the work of those reporters over time. “Those who correct themselves also are good,” he said.

He said the mainstream press, currently being targeted by the White House, must resist being de-legitimized. “Don’t get knocked off stride or play tit-for-tat, which is his game,” Rosen said would be his advice to journalists, “and don’t be defensive and get caught in a war of words. Just listen to what they say, be polite, then do the work. Be calm and cool.”

But he would tell the embattled press that, while staying calm, they should stay aware that “an organized movement in the country to discredit the press is a real thing that reaches into the White House and spreads from there … so they have to report on that — tell the public, and equip citizens to fight back.”