College expecting ash borer impacts, costs

The big tree in front of Founder’s Hall (at right in the large file photo above the headline) is an ash tree that might soon be threatened by the invasive emerald green ash borer, seen in the stock image above.

Saint Michael’s College is preparing for the inevitable eventual campus impact of an insect called the emerald green ash borer, which has arrived in Vermont with the first known specimen in the state being identified recently in the central Vermont town of Orange.

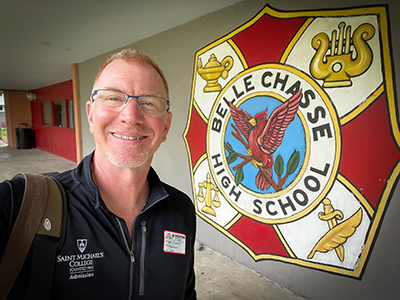

About 85 ash trees are planted around the campus of Saint Michael’s — it used to be closer to 130 until some recent building projects that required the removal of some. Once the borers arrive (that could be anywhere from months to years from now) the College basically will have two options, and neither is cheap, said Alan Dickinson, the College’s associate director of grounds, special services and transportation.

“Right now, unfortunately, they don’t really have any control over that pest – some insecticides work by tree injection and through the soil” said Dickinson — but it only lasts two years and then requires another pricey round of fresh injections for all 85 trees.As Dickinson sees it, the College’s options once the insect arrived would be to pay for those regular insecticide treatments on all the ash trees, which could run as much as (he only very roughly estimates) something like $25,000 every few years, or plan for “a major tree take-down” operation, which also would not come cheap and eventually would require a large replanting effort around campus that would carry further cost.

Dickinson is knowledgeable and passionate about trees, and knows the story of nearly every tree on campus. He’s had the ash borer threat on his radar for years — ever since the pest, native to Asia, began spreading as an invasive species across North America from the Midwest in about the late 1990s, killing millions of trees.

Without ash trees, the Saint Michael’s campus would look significantly different, with noticeably diminished shade and landscaped beauty, said Dickinson. Some prominent ash trees include the huge one outside the president’s office on the lawn by Route 15, another beside Prevel Hall across the street, two beauties that he planted himself by the library, and quite a few surrounding the residence halls from Cashman down to the new building — and also along the road by the 300s near Gilbrook Recreation area.

“Even if we treated them once – if, down the road, you don’t treat for a year, then they’re all susceptible,” he said. Another factor is that Dickinson doesn’t have the size of crew needed to administer insecticide to so many trees, alongside existing duties. Further complicating matters is that trees keep growing, so if one round of insecticide is used, in two years all those now-larger trees will cost even more to remove if it comes to that. “It’s is a challenge and I don’t know what direction Saint Michael’s is going to go,” Dickinson said, adding that he and Director of Facilities Jim Farrington this week had some preliminary discussions about their options in light of the recent ash borer news.

“Usually experts don’t recommend treating until the borer get 50 miles from your site,” said Dickinson, observing that Orange, VT is not much more than 50 miles away. “It’s getting closer,” he said, “and who knows what other infestations they haven’t discovered yet?”

Currently experts know of no biological controls such as predator insects that might control ash borers. “Once they get here, that’s it,” he said. “Places like St.Mike’s are vulnerable.” His personal best advice at this point would be “cautiously promoting” the use of the insecticides if the insects get closer – “maybe treat for two years and figure out where we’re going to go, giving us the time to come up with a tree replanting plan,” Dickinson said.

Other than considering a fire wood quarantine on Orange County, Dickinson is unaware of any specific measures planned by the state of Vermont to control the ash borer at this time. “We’re going to be impacted in Chittenden County to some extent,” he said.

In a 2011 interview about campus trees, Dickinson spoke of another bug from China, the Asian longhorn beetle, saying there were no known controls if that ever got on this campus — “Plus it affects more species, maybe 10 to 12 varieties, and if they come, the only recourse is to cut down the affected trees and chip them, so there are some real concerns as a grounds manager,” he said.

Campus Tree History

Dickinson carries forth a rich oral tradition about campus greenery handed down to him by his mentor and predecessor, the presciently-named Forrest Procter, a former grounds crew leader who was a forester by trade when he launched an earnest and purposeful campus planting campaign in the 1980s. Procter soon had a kindred spirit in Dickinson when he hired him in 1984 and their efforts have essentially shaped the contemporary foliage landscape at Saint Michael’s in recent decades.

One of Procter’s lasting legacies is the unusual variety of distinctive species that he introduced to the campus landscape. Some notable and prominent examples were an American Chestnut along the north side of the chapel, some Liberty Elms near the quad (it’s a species specially bred from old fashioned Dutch elm stock to be hyper-resistant to disease, Dickinson explains) and some distinctively-shaped and beautiful but extremely slow-growing Asian Gingkos along the diagonal center walkways. Alongside other buildings and walkways, within the rectangular area delineated by the quad, St. Ed’s, the chapel and the library, are also pleasing rows of pin oak and Norway maple, blue spruce, silver maple, Canadian hemlock, purple-leaf sand cherry, linden, basswood, burr oak, white birch, balsam, crabapples and more.

“When I first came we were right on the heels of a lot of elm trees dying of Dutch elm disease,” said Dickinson in 2011 as he stood outside the President’s Office entrance by the big lawn at the Route 15 curve. “This whole front here near Founders, if you look at old pictures, had probably five or six huge elms on this lawn, so the canopy over campus was exceptionally beautiful.”

The sad whole-scale loss of those classic majestic beauties of the American landscape drove home an important lesson for anybody strategically populating a college campus with trees, said Dickinson. “The real rule of thumb on a college campus or landscape is to keep your tree species less than 10 percent of any one kind so if you have a disease or insect that comes through, you don’t lose every tree on campus to one natural occurrence,” he said.

Ash trees, however, are disproportionately popular with landscapers for several good reasons, said Dickinson, who mentioned in particular the large one outside the president’s window that he estimates to be 50 years old, even though a slower-growing oak might take 75 years to achieve the same size. “They grow very fast, and ash was native to New England, so this and other specimens on campus might have naturally occurred rather than being planted,” he said.

Also, the variety is known to be “a really tough urban street tree” that tolerates a lot of road or sidewalk salt in winter that easily can get plowed around their roots. That contrasts sharply with, for example, sugar maples, which simply will not tolerate salt. A species that does well would be hackberry trees, which he called “very specific to this area – hackberry seem to really like the soil around Saint Michael’s. There’s probably 5 or 6 campus-wide, one in front of Prevel, one in the center if campus. We probably should try to plant some more – they seem to do pretty well,” said Dickinson.

Peter Hope of the biology faculty, a botanist and plant taxonomist, says the borer-vulnerable white ash outside the President’s Office — a specimen of Fraxinus Americana — is “probably my favorite tree on campus. I love the bark on white ashes – fairly sharp ridges and canoe-shaped fissures and very homogenous all around.”

“I’ve joked with students that if I ever see someone coming at this tree with a chain saw, the students are going to have to bring food and water to me up in the tree,” Hope said.