Lecture on liberal arts benefits

Columbia scholar celebrates liberal arts in Sutherland talk

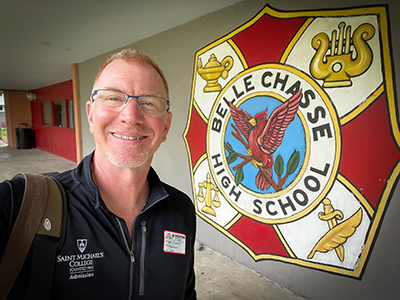

Directly above, Roosevelt Montas is at right, with with VPAA and Dean Jeffrey Trumbower; below, the audience at the evening lecture, with individuals offering dialogue and questions in photos below. (photos by Danielle Joubert ’20)

Columbia University scholar Roosevelt Montás (Ph.D.) offered a robust and clear articulation of the values of a liberal arts education as well as a personal testimony to its centrality in his life and career last week when he delivered Saint Michael’s College’s 2019 Sutherland Lecture, as he did earlier the same day during an afternoon visit to Professor John Izzi’s philosophy seminar on Heidegger.

Saint Michael’s College hosted its annual Sutherland Lecture on Thursday, February 21, inviting Montás, senior lecturer in American Studies at Columbia University, to present to an audience of Saint Michael’s students and faculty for the main evening presentation, following the seminar session. His talk, titled “Liberal Education and Human Freedom,” served as a vivid defense of liberal education: the kind of student-oriented learning necessary for freedom, active citizenship, and fully-realized humanity.

Montás, who recently began teaching full-time at Columbia in addition to his administrative role at the university, specializes in Antebellum American literature and culture. He has a specific interest in American citizenship and national identity, explored in his 2004 Bancroft-Award-Winning dissertation, “Rethinking America: Abolitionism and the Antebellum Transformation of the Discourse of National Identity.” As a professor, Montás teaches both Literature Humanities and Contemporary Civilization.

As a scholar of culture and as a senior administrator in selecting the core curriculum at Columbia, Montás is particularly concerned with how education functions in society. During both his visit to Professor John Izzi’s Philosophy seminar and his presentation in the evening, Montás articulated the value of a liberal arts education to all people in a liberated society. His arguments were rooted in history and philosophy, with references that spanned from Plato to Freud. “In ancient Athens,” Montás said in his Sutherland lecture, “liberal education was thought of as the kind of education that is appropriate for the free citizen.” The reverse was also true; slaves were deliberately denied liberal education, as Athenian society did not mean for them to be liberated.

As a scholar of culture and as a senior administrator in selecting the core curriculum at Columbia, Montás is particularly concerned with how education functions in society. During both his visit to Professor John Izzi’s Philosophy seminar and his presentation in the evening, Montás articulated the value of a liberal arts education to all people in a liberated society. His arguments were rooted in history and philosophy, with references that spanned from Plato to Freud. “In ancient Athens,” Montás said in his Sutherland lecture, “liberal education was thought of as the kind of education that is appropriate for the free citizen.” The reverse was also true; slaves were deliberately denied liberal education, as Athenian society did not mean for them to be liberated.

“Liberal education,” according to Montás, “teaches you how to be free.” The essential element of an education that propagates freedom is a complete focus on the student’s own development. What some would consider to be aimlessness may actually be the very soul of the exercise: not for the student to have no aim, but for the student to be the aim. Any concrete goal outside of the student’s development misses the point. “The student, the individual as a growing entity, is at the center. The subject here is secondary,” Montás said. “The very fact of learning this way is an exercise in freedom. It cannot be compelled. It cannot be coerced. You can only be liberally educated through an affirmation of your irreducible individuality, of your moral autonomy… your dignity.” One of the most difficult things for new college students, Montás offered as an example, is learning to self-govern and to manage one’s personal responsibilities without any micro-managing authority.

While Montás readily acknowledged the importance of specific career training, his talk illuminated liberal education as a separate, crucial entity that should be accessible to all at every level of education. He stressed the dangers of an exclusive devotion to productivity, of following our natural human tendency to want more. “Our fear of not having enough drives us to hoard, accumulate, and to enslave our lives to what is literally a never-ending quest for more goods and more security,” Montás said, applying this principal to industry, our destruction of the environment, and something as simple as our physical drive to overeat. When it comes to building a better society, we’re fighting against out own evolutionary need to over-consume. “This hunger runs deep in our psyche,” Montás said.

A liberal education is concerned with something higher than that. Beyond doing the necessary work to support ourselves and each other as physical beings, there’s the formation of the individual. “There is a certain kind of cultivation,” Montás said “that is required for the exercise of citizenship. That can only happen if you have room in your development to dedicate to matters other than simply making a living.”

A liberal education is concerned with something higher than that. Beyond doing the necessary work to support ourselves and each other as physical beings, there’s the formation of the individual. “There is a certain kind of cultivation,” Montás said “that is required for the exercise of citizenship. That can only happen if you have room in your development to dedicate to matters other than simply making a living.”

Montás’ own methods of citing relevant information throughout his lecture would point to the importance of historical and philosophical literacy as a core element of liberal education. But to exemplify the irreducible value of liberal studies, he selected great literature as the major talking point, crediting it as “the absolute best way we have of approaching the experience of what it is like to be someone else.” His primary example of such a work was the Iliad, which he noted as illuminating the human condition of mortality by comparing its mortal characters with the more immature, thoughtless gods. But of course, even Montás’ own summary couldn’t do justice to classic literature. Great literature, much like a liberal education at large, works because it is an experience rather than simply a form of instruction. “Great literature is challenging,” Montás said. “It demands effort and sustained attention to yield its deeper meanings. You have to pour yourself into a great book in order to get what it has to offer… you can only get what it has to give by experiencing it as it is.”

The floor was open for both question and comment after the lecture was finished, with students, faculty, and staff all stepping up to engage in a larger discussion. There was concern for methods of assessment in higher education, how these principles should apply to children and high school students, and how false political implications have seeped into the terminology of “liberal” education. Lively discussion was a fitting conclusion to the lecture, since these conversations are the kind best carried out by liberally educated minds in the view of Montás. The moral and intellectual foundations that we should all have as democratic citizens, for instance, are sought after through liberal studies. But even if one were to live a solitary life, Montás argued, liberal education would still be valuable. The individual should be fully realized not only for the sake of society, but for the individual’s own sake.

The floor was open for both question and comment after the lecture was finished, with students, faculty, and staff all stepping up to engage in a larger discussion. There was concern for methods of assessment in higher education, how these principles should apply to children and high school students, and how false political implications have seeped into the terminology of “liberal” education. Lively discussion was a fitting conclusion to the lecture, since these conversations are the kind best carried out by liberally educated minds in the view of Montás. The moral and intellectual foundations that we should all have as democratic citizens, for instance, are sought after through liberal studies. But even if one were to live a solitary life, Montás argued, liberal education would still be valuable. The individual should be fully realized not only for the sake of society, but for the individual’s own sake.

“A liberally educated life,” he said near the end of his lecture, “will be richer than other lives. It will be more true. It will be more awake.”