Rabbi Wall speaker explores Jewish environmentalism

By Zoom from Israel, scholar, author and activist Alon Tal shares an ancient tradition's unique insights on global challenges

Professor Alon Tal presents the annual Rabbi Max Wall lecture for Saint Michael’s College from Israel via Zoom in this screen grab from Monday’s talk.

Jewish environmentalists are widely enthusiastic and optimistic in embracing technology to advance the cause, unlike many outside Judaism who might hold technology more suspect for being beyond immediate organic nature, said Alon Tal, a scholar, activist and policy official who spoke from Israel by Zoom for Monday afternoon’s annual Rabbi Wall Lecture for Saint Michael’s College.

Tal’s topic was “What is Jewish about Jewish Environmentalism?” Much as technology allows precious water to be produced through advanced desalinization, then efficiently dispersed in the dry land of Israel or shared with neighbors, so, too, on Monday did technology allow Tal’s fertile insights and historical-spiritual perspectives to soak in for nearly 80 participants in the Zoom lecture. They ranged from St. Mike’s students, administrators, faculty and staff to members of the greater Burlington Jewish community and other interested scholars — some invited by the late Rabbi Wall’s family who also took part. In a non-pandemic year the lecture typically is held on campus with similar numbers attending.

Tal at one point cited an ancient Talmudic debate that allows the conclusion for most Jews that “we receive a world that’s imperfect in which human participation is important – we’re allowed to get engaged and change things (I.e. through technology) since that’s the nature of human existence.” He quoted a popular Jewish novelist’s words that “nature is not a museum” to further this point.

Jeffrey Trumbower, Saint Michael’s College vice president for academic affairs, introduces Alon Tal during Monday’s Zoom lecture.

Jeffrey Trumbower, the College’s vice president for academic affairs, introduced the speaker, who is a professor of public policy at Tel Aviv University and environmental health policy specialist, lawyer and prolific author. Tal made clear in his talk that his environmental concerns are broad and cast a wide net, including cooperative work with Palestinians and Jordanians among others. The talk posited that the Jewish perspective has unique insights and approaches to the global challenges of sustainability, exploring how the ancient Jewish tradition perceives humans’ relations with the Earth and why it is relevant today.

For a framework early on, Tal drew partly from the scholarly work and activism of one notable participant in the Zoom lecture, Rabbi Michael Cohen, who lives in Manchester, Vermont but spends a lot of time in Israel, and who has a close connection to the speaker and other Israeli environmental leaders. At one point about 15 minutes into Tal’s talk, Cohen voluntarily “pinch-hit” to share some of his own expertise during a short temporary glitch with Tal’s Zoom connection that was soon restored.

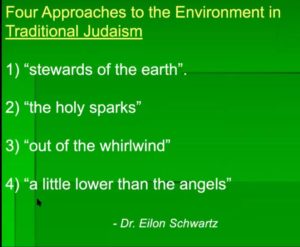

Among Tal’s framing ideas, drawn from Cohen and from Dr. Eilon Schwartz were: that Judaism regards humans as “stewards of the earth” as a very strong tradition, traceable back to Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. He said God essentially tells Adam in Genesis, “Make sure you don’t destroy these things, no one can replace them”– so there’s “this tremendous sense of responsibility” in Judaism to preserve the natural world. A more mystical perspective he referred to was the notion of “the holy sparks,” in which even stones can have divine presence and the Almighty can be found in all things, meaning reverence to the natural world is inherent in the Jewish mystical tradition. He spoke also of what he called an idea of “Out of the Whirlwind,” as in the book of Job where a sense of humans’ smallness, but also capacity for joyfulness in creation, is accentuated, with humans a little lower than the angels “though on top of the food chain.”

Tal used slides in his presentation to communicate main points. One showed a list of things he finds unique about Jewish environmentalism that might be worth considering, including:

- The authenticity of antiquity and the exciting inspirational quality of the ancient – he noted how the Tower of Babel story is a parable about excessive reliance on technology, and how the story of Noah has a central theme of biodiversity and the importance of protecting nature. He spoke extensively about trees and how rain patterns in different parts of Israel figure into aspects of holidays like Passover or Sukkot. He marveled at words from a rabbi in Egypt 2,000 years ago who seemed to anticipate climate change in its many aspects

- That Jews often “think locally about Israel but act globally.” The speaker’s references on this and the previous point included the agrarian biblical story of Ruth gleaning (among his personal favorite stories, he said); or the Philistines inhabiting the coastal areas versus the mountain-dwelling Israelites of old and how that shaped history, all relating to geography and environment and weather to those who dig more deeply into it.

- That Jewish history is built largely on an agrarian tradition and history, although today, while Israel is very innovative in farming, only 2 percent make a living at farming so that is a fundamental change to reckon with compared with ancient times.

- The “technological optimism” previously mentioned that informs Israeli environmentalism.

- Environmentalism as an expression of the underlying commitment in Judaism to social justice. “Environmental justice” is an important movement in the U.S., and that’s a central part of Jewish perspective, with a sense of responsibility for the world that is contained in Jewish prayers and ethos. Tal said his wife works for an NGO that brings some of Israel’s environmental technology to parts of Africa where it greatly improves people’s lives.

- The idea that the Sabbath is seen traditionally as “a day you don’t change the world,” but rather look at creation so as to simply ponder and appreciate it. ”One day we need to stop and be in harmony with the natural world,” said Tal. “I was told the Sabbath was created for a sort of re-creation of the Garden of Eden.” He suggested it is good for humans to just “listen to the Earth a bit,” regularly, as on the Sabbath for Jews.

After the lecture came a question and answer session. One came from Rabbi Amy Small of Burlington’s Ohavi Zedek Synagogue, which was the congregation originally led by the late Rabbi Wall. Wall, after whom the lecture series is named, was a war hero and beloved figure throughout the Burlington community for decades (and also a onetime Saint Michael’s religion instructor and friend of the Edmundites). Rabbi Small asked about environmental damage in the Dead Sea area that she had seen during travels to Israel with a group in recent years.

Rabbi Amy Small

Tal explained how water from the Jordan River flows to the Sea of Galilee and used to spill into the Dead Sea, but in a “zeal to make the desert bloom,” most of the natural flow is gone, so the Dead Sea is shrinking. He said it put him in mind of a parable that likens the Sea of Galilee — “taking the rainfall and sharing” — and consequently so being full of life, while the Dead Sea “keeps it all to itself” and is thus a terminal lake; much as with humans who share with others typically are full of spiritual life, as opposed to the relative death of those who to keep everything to themselves. He said he would dearly love to have the River Jordan flow again but it would be prohibitively costly; also, climate change has lowered rainfall in the region 20 percent so that restoring natural flow is not a practical option now. “We cannot be the generation that lets the Dead Sea die,” he said he often thinks — but the solution likely will have to be technological now, such as a canal from the Red Sea.

Rabbi Michael Cohen said he thinks about the apparent contradictions in Genesis present in its precepts for humans interacting with earth, raising questions: Should humans be stewards as one part of Genesis suggests, or have “full dominion” of the earth, as another portion says. His answer is, “we are both” — that part of being humans means having a nuanced and sophisticated approach to the environment and the tensions inherent to our interaction with it.

A slide shared by the speaker shows expected profound results of climate change in coastal Tel Aviv.

In response to a question from Nat Lew of the Saint Michael’s fine arts faculty, Tal said that a sad truth in Israel now is that “the quantity of life is starting to affect the quality of life,’ given the perpetual recent very rapid population growth, all in a very finite ecosystem. “People have to talk about it – it’s taboo and has religious concerns and is very charged,” he said, “but nature and the environment don’t really care about that.”

The speaker’s closing comments credited Vermont with its lively spirit of environmental restoration and reclamation that “produces an optimism we desperately need,” adding, “The problems are much too serious to leave this as a spectator sport — so I want to thank Vermont for being an environmental leader in many areas.”