Inaugural Edmundite scholar shares her work, life influences

In describing and demonstrating what community looks like, Jolivette Anderson-Douoning presents dissertation findings on the Black experience in America, based on research into generations of her own family's history in Louisiana over the past century

Jolivette Anderson-Douoning presents her research findings Tuesday, November 9 in the McCarthy Arts Center Recital Hall. (photos Lauren Read)

Watch a recording of the full presentation>>

In her absorbing and challenging telling of the Black experience in the U.S., Saint Michael’s College’s Inaugural Edmundite Graduate Fellow on Tuesday solidly checked all the academic boxes that such a research-based lecture demands, yet it was the presenter’s warm, direct and honest personal human connections that stole the show.

Respect for elders and appreciation for communities — from the Louisiana neighborhood of her youth to Saint Michael’s today — shone through from the first words of Jolivette Anderson-Douoning’s late-afternoon presentation. The speaker thanked and honored Margaret Bass, President Lorraine Sterritt’s assistant for diversity and inclusion, who, she said, primarily convinced the speaker to come to Saint Michael’s, and has “had her back” through the major adjustment of moving cross-country from Indiana with her 15-year-old daughter Nadja (in attendance, with the lecture dedicated to her).

While finishing her dissertation as a Purdue University PhD candidate, Anderson-Douoning has been teaching in the Saint Michael’s History Department this semester with Professor Kathryn Dungy, who introduced her co-teacher Tuesday to a good-sized audience in the McCarthy Arts Center Recital Hall.

Listeners included faculty, staff and students — a few from this semester’s “BIPOC Resistance and Power” course taught by “Professor J,” as class members lovingly call her, according to co-teacher and introducer Dungy. Many others were able to tune in on Zoom and watch, including (the speaker noted later), friends and family from the Shreveport, LA, “Hollywood” neighborhood where Anderson-Douoning grew up. Those roots focused and vividly animated Tuesday’s lecture, providing concrete and personally resonant examples to illustrate points about the lived Black experience in a relatable microcosm.

Anderson-Douoning’s dissertation title is “LOUISIANA LEARNING: Race-Space Geographic Education and the Creation of Black Cultural ‘Place in Shreveport’s Hollywood Neighborhood on Ledbetter Street 1945-1985.” Her 90-minute presentation about it included PowerPoint slides.

Kathryn Dungy introduces the speaker Tuesday.

As Dungy noted in her introduction that this year’s Edmundite Scholar identifies five “Black Spaces” of African-Americans’ lived experiences – family, school, church, the work industry and the leisure/play industry — and “utilizes a variety of historical and cultural research methods to build her theoretical and cultural framework.” Anderson-Douoning shared a series of examples from her own family and neighborhood history, culled from archives, oral histories and other sources, including a good number of photos.

After opening by presenting a gift of a beautiful fern plant with symbolic meaning to “Mama Bass,” as she affectionately called her campus mentor, Anderson-Douoning got into the meat and potatoes of her presentation. She interspersed personal asides and insights with good-natured humor that observably kept her audience engaged, all while making academic points from her studies.

She said her work deviates from the strictly academic realm and “moves to talking and listening with all people about who they are, where they are, and how they got here … [and] The same question I ask human beings, I also ask of the institutions that run our lives.”

She said that the previously mentioned institutions that her research questions — family, school, church, work and play – are areas that she likes to think of as existing in “houses.” The term properly communicates those sites as “a place — and a space within that place — to go to” that is sheltering and comfortable, as with one’s family home — be that the church, school or other neighborhood centers.

Anderson-Douoning got some appreciative chuckles by illustrating a point with the example of moving to Vermont and hearing about the need for snow tires – that is, learning the necessary means to thrive and survive in a given environment, much as Black people have managed to do through these familiar “houses” in their daily lives.

PowerPoint slides behind the speaker helped her make her points.

“If the academic cannot explain to others how and why what they teach, research and attend conferences about, impact the everyday lives of everyday people, then they are disconnected from what really matters – including and especially the Black lives that we say matter – and that disconnect is dangerous for all of us,” she said.

She emphasized how much our language matters in discourse on any topic but particularly race issues. The speaker spent some time carefully explaining and defining terms relevant to the conversations that she hopes to advance in her work regarding Black people through historical periods, as illustrated through six generations of women in her own family going back over 100 years in Louisiana.

In the more academic terms of her PhD work, she said, racial interactions and processes are about “how we collectively make and remake, over time and through ongoing contestation, the spaces we inhabit.” She spent some time painting an interesting human picture of life in her home Hollywood neighborhood (that has produced Boston Celtics basketball great Robert Parrish and CORE Civil Rights activist David Dennis). The examples from her family history aimed to answer questions, she said, including: Why have black people been mistreated in the U.S., or labeled inferior, and what stereotypes have existed through the nation’s history about Black people, and why? She also spoke briefly about work she did with Civil Rights hero Bob Moses in Mississippi in making other points.

“I look at the world from the perspective of what the citizen says is happening in their lives,” she said. Some of her PowerPoint slides had strong visceral impact – for instance, showing young Black children in the South from a newspaper clipping in the 50s or 60s, dressed up and excited to be going to the fair on the one day the white and officially segregationist majority “allowed” them to attend. Also, she shared photos of the teachers and administrators at a neighborhood school — among them the speaker’s mother – describing the inspirations they provided for her and others.

Several times during her talk, Anderson-Douoning acknowledged the Edmundites — resident founding religious order at Saint Michael’s — for their support of her scholarship and for their longstanding work in Civil Rights in Selma and other locations. She specifically noted the Edmundite Superior General Fr. David Cray in the audience, as one of the “elders” (over 70), from whom at the outset, in her tradition, she sought permission to speak.

Anderson-Douoning takes questions from the audience after her presentation.

The question-answer session after the lecture was lively and interesting.

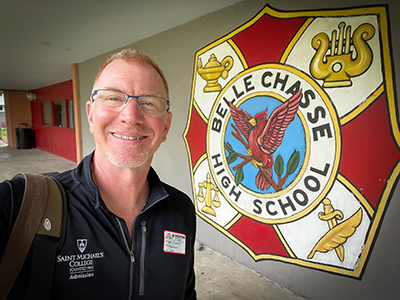

Stanley Valles, the College’s new director of public safety, asked the first question: “With so many places you could have gone, why St. Mike’s? Anderson-Douoning answered that Margaret Bass was the biggest reason she came, since her now mentor and friend knew so many prominent scholars who encouraged her to look at the opportunity, while assuring the support of unvarnished truth telling of what to expect once she arrived. “I felt I could find community here,” the speaker said.

Students she has met personally already this semester also asked questions that were both insightful and personal about racial identity, partly based on things they have been learning in classes, and those interactions revealed the meaningful close connection they have now forged with a new wise member of the community. This came through especially in Anderson-Douoning’s thoughtful extemporaneous answers that sometimes used endearment terms common in Southern culture, such as “beloved” or “my daughter.”

Jeffrey Trumbower, vice president for academic affairs, poses a question Tuesday.

The scholar said near the end of Tuesday’s program that she would present “part two” about her work during a lecture next semester, when she hopes to speak about her grandmother’s work in a chair factory and picking cotton, and how her grandmother’s years of labor in those industries relate meaningfully to the larger American story.

After the lecture, the Edmundite Fellow said the experience of making her presentation was interesting to her on several levels – she was comfortable before a crowd on the one hand since Anderson-Douoning has a background in theater — but nervous too, wondering “how did I make these difficult things to talk about not offensive.”

She explained: “When we talk about race and culture, people don’t always know how to respond, so I was trying to be careful, but genuinely myself, genuinely representing the authenticity of the community I come from at the highest level, being honest about the highs and lows of everybody’s community.”

The presenter said she tried to strike a balance between not romanticizing where she grew up, but also showing that it was a supportive and vibrant place, full of life, and not a fearful place as many common stereotypes might hold and assume simply for it being a “Black neighborhood.”

She said the issues she addresses, by their nature, “can occupy the psyche” in powerful ways, so she takes care “not to exhibit attitudes or behaviors that make me be what I say is not correct. If I say somebody has oppressed me, I don’t’ want to turn around and do the same thing, which requires an honest conversation with one’s self…stepping out with that self-knowledge and making decisions about how you want to function in society.”

A larger goal for her work, Anderson-Douoning said, is that it might be “a stepping stone to colleges to attract and engage and maintain domestic Black students,” as at Saint Michael’s.

“I know I come from decent people and am trying to be a decent person,” she said during an answer to one student question. “We must give ourselves time and space to grow, but we have to ask the questions [as individuals and institutions]. If we don’t ask questions, the answers aren’t going to come — and it’s lifelong work.”

“It gets to the basic level of how do you want to be treated?” she later said. “I have a voice, and I use it.”

An important message appears on the screen behind the speaker Tuesday.