The Life and Dignity of the Human Person in the Context of Life’s Realities

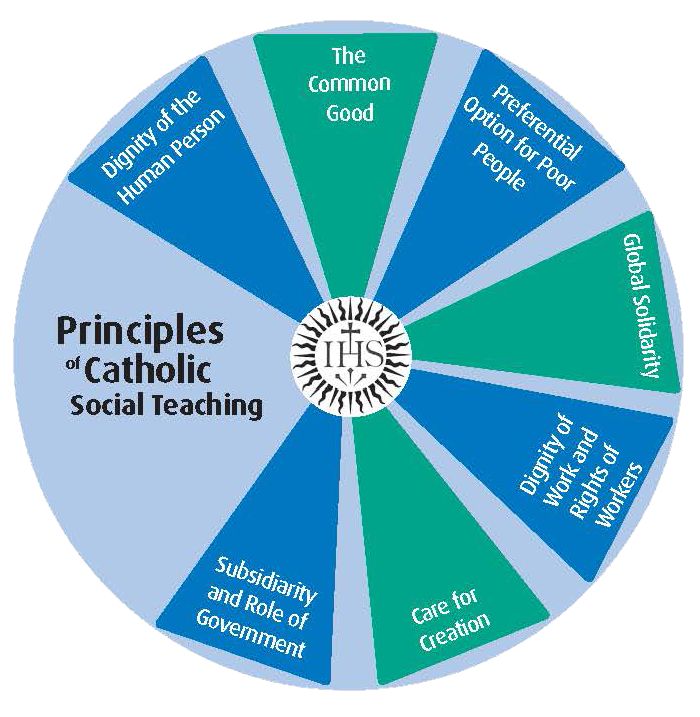

I feel compelled to say something more about the first Catholic principle of social justice: life and the dignity of human life. What is driving this compulsion is the present reality of our lives in the United States, rooted as they are in a quagmire of political and social factions that move people to be more concerned with “prevailing” over others in their difference than in finding “common ground” on which to thrive as a nation. This “common ground” can also be envisioned as our common good, a fundamental principle of Catholic Social Teaching that envisions a condition of society such that all in society, both collectively and individually, possess the greatest possibility of flourishing. Is this not also the purpose of the principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion: the full inclusion of everyone in their difference, with equal access to all the benefits of society?

As imagined, however, this ideal of human thriving can become fixed in a set of prescriptions for shaping the common good that, ironically, become judgments on the realities of life that people encounter—and indeed on the people themselves whose lives are described by these realities. Promoting the Catholic faith as the true faith can quickly devolve into a devaluing of faith commitments outside the Catholic Church and a condemnation of those who, without fault, find that they cannot believe. Upholding the integrity of faithful love in marriage has become for many a perceived indictment of their failed marriages. The Church’s conviction that marriage is between a man and a woman can readily lead to the assumption that other forms of union among LGBTQ+ persons are by necessity invalid or indecent.

Pope Francis reminds us that “reality is greater than ideas” (Evangelii Gaudium no. 231; see also Fratelli Tutti no. 222). He urges us to understand that the ideals the Church promotes about human flourishing must be approached through people’s real lives: their concrete hopes, struggles, and experiences. For Pope Francis, this is not a dilution of the Church’s mission; it is its deepest and truest fulfillment.

Those who are divorced, those who identify as LGBTQ+, those of other faith traditions, and those of no religious affiliation are not “outside” the Church or “beyond” its scope, except by a definition that elevates the ideal over the real. The Church is not a gathering of the flawless, set apart from the world’s imperfections. It is a community of people, each seeking to live authentically amid the complexities of life, who encounter the same realities as others. Thus, for Saint Michael’s College to be truly Catholic, we must embody this understanding by embracing all students, faculty, and staff as fellow pilgrims walking together toward truth and meaning.

We are to be a college that practices accompaniment, not judgment. Jean-Luc Marion, especially in God Without Being and Being Given, cautions against making an idol of our own ideas—treating them as ends in themselves rather than opening ourselves to the true God, who is always greater than any concept or ideology. When ideas, even religious ones, become rigid and closed, they risk becoming idols. This insight parallels Pope Francis’ warning against “ideological colonization”, wherein ideas are imposed on others without regard for their lived realities and dignity. True Catholic education resists this temptation by privileging encounter over imposition, dialogue over domination.

Mahalia Jackson’s memorable saying, “Some people are so heavenly minded that they are no earthly good,” further challenges us. Faith that withdraws from the struggles and questions of real life becomes sterile. Authentic faith, by contrast, enters deeply into human experience with compassion and humility.

Catholic higher education is thus called not merely to teach ideals, but to form a community where all members, especially those who have experienced marginalization, are fully valued. Those who have felt alienated from the Church are not anomalies; they are part of the Church’s living body, sharing in its hopes, wounds, and possibilities.

The work of Catholic social justice is both humble and hopeful. We are not tasked with creating a perfect community from above but with accompanying one another toward a fuller realization of God’s desire that we thrive in company with one another. In honoring each person’s dignity, fully recognizing that all of us bear the marks of imperfection and grace alike, we live out the Church’s true mission: to be a communion of real people seeking together the fullness of life, our shared common good. That some identify as Catholic, and others find their identity in other faiths or no faith at all, should not blind us to the deeper truth: we are all equally part of the human family, deserving of being valued and respected for who we are and not according to what others say we should be.

If you would like to make a comment or ask a question, please feel free to contact me at dtheroux@smcvt.edu. Let’s talk.

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.