A shortened version of this Q&A is included in the Spring 2025 edition of Saint Michael’s College Magazine.

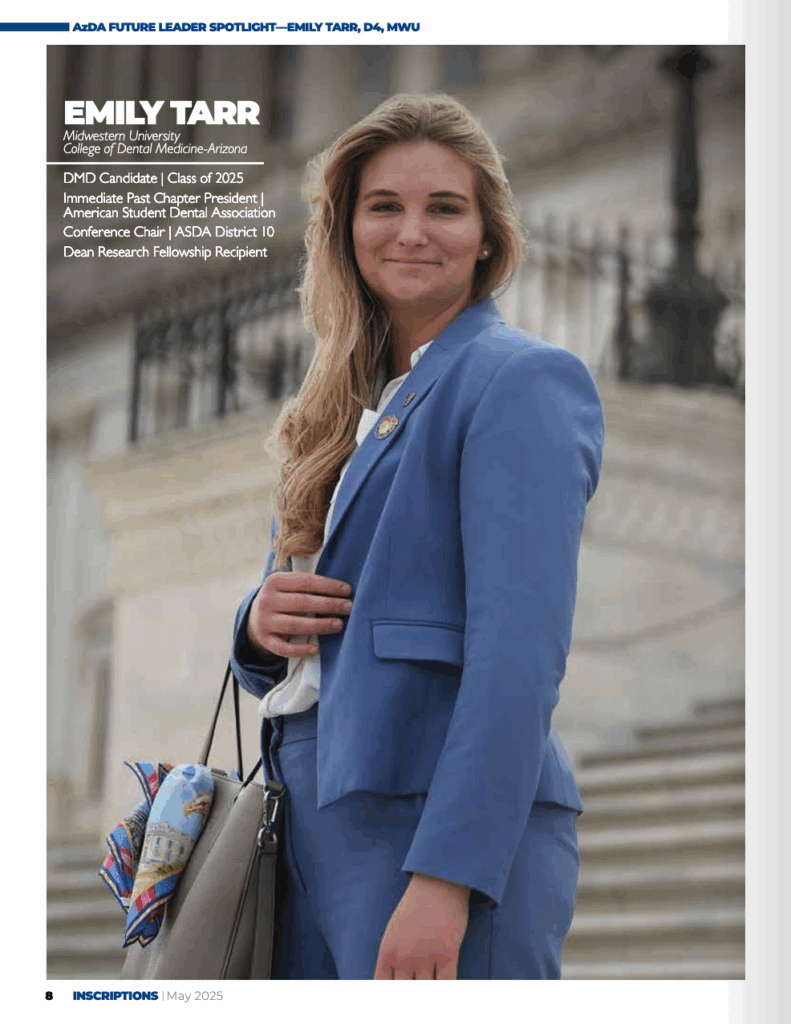

Kristin Dykstra, distinguished scholar in residence and director of the First Year Seminar at Saint Michael’s College, is making waves with her 2025 book, Dissonance. Winner of the third annual Phoenix Emerging Poet Book Prize, Dissonance dives into contemporary themes with depth and originality. It was also chosen by Admissions for the 2025 Saint Michael’s College Book Award. In this Q&A, Dykstra shares her thoughts on her writing, winning a prestigious award, how poetry migrates into the classroom, and how literature sparks conversation and critical thinking.

Saint Michael’s College: Why did you choose Dissonance for the title of this collection of poetry?

Kristin Dykstra: It’s a flexible term, permitting many interpretations. I considered different titles along the way. These focused on the foothills and ridgelines around the dirt road at the center of the book, because place plays a big role [in it]. But two poets who saw the manuscript, Cal Bedient and Urayoán Noel, argued for Dissonance instead. I’m grateful that they did, because I can now see that they were right.

Here are a few things channeled into the title. I grew up around a lot of music, and while harmony gives us pleasure, it speaks most powerfully in partnership with moments of dissonance. I was also thinking about writing something that resists reducing Vermont to stock imagery from marketing (especially for tourism) and media—a work that would open more deeply into the space, into the realities that people live. There’s also a connection to the field of 21st-century poetry: I’ve been interested in contemporary works that explore the use of research, which takes us outside our own individual points of view on the world. In creative works encompassing research, there’s a fundamental tension between one’s own perspectives and what we learn to see through other people. Learning from this tension helps me think about relevance.

SMC: How does it feel for your first full-length book of poetry to be recognized with the Phoenix Emerging Poet Book Prize from the University of Chicago Press?

KD: It came as a total surprise—I didn’t expect Chicago to publish Dissonance, let alone recognize it with the prize. The Phoenix Poets series goes back to the 1980s, and it’s a great honor to become part of their list. Representing the press at events means that I get to spend time with fellow writers who are doing current, impressive projects of their own. It’s energizing to be in that space.

SMC: Do you incorporate poetry into your lectures and lessons in the classroom at Saint Michael’s? If so, how?

Kristin Dykstra, scholar in residence and director of First Year Seminar

KD: The classes I teach are interdisciplinary, centered on topics about which the students know very little, since they aren’t taught in K-12. This means that we need to give time for background context, along with any literature. For example, I’ve been publishing translations of Latin American writing for a long time, and I teach two courses that introduce students to Latin American countries, in a survey format. We have to cover a lot of history to get started. The poetry I can include in this format is limited.

So what happens? My seminar students have rarely studied poetry itself, or even much literature, at the college level. Yet these same students gradually learn to see how our literary selections animate tensions they’ve been learning to spot in the social histories. So this class format has interesting results.

Coming from this angle, you can see how relevant the literature is—how it is part of a bigger, dynamic conversation in and across societies. Students start to see the range and diversity of what people have created under this umbrella term, poetry. Furthermore, I think this approach may help to unsettle popular stereotypes about poets, so that we can better understand why this art form remains important around the world.

This spring, my Junior Seminar included a quick introduction to Gabriela Mistral (Chile, 1889–1957; Mistral was the first Latin American to win the Nobel Prize for Literature). As usual, I have a lot of students who started out making comments along the lines of “I’m bad at this; I don’t understand poetry.” But you should see how sophisticated their remarks actually became, a couple of months into the semester. They just don’t know in advance what they can do. Now, what I’d really love to see is what some students will start creating 10 or 20 years into the future.

SMC: Where do you draw inspiration for your own poetry?

KD: Robert Creeley (1926–2005) was teaching in Buffalo when I got there. He’s known for saying, “Poetry is a team sport: you can’t play it all by yourself.” I never actually heard him say this famous line, but he was part of a group of poets who modeled the idea for us. You build creative community, and this community can be at once demanding and generous, challenging and supportive. These days my community is more dispersed around the country, instead of concentrated in a city.

Meanwhile, I’ve seen poets from other countries work similarly to create and maintain creative community. Reina María Rodríguez, with whom I’ve worked as a translator for decades, is known for [her years of] running an independent salon. She made creative conversations possible in the city of Havana. You don’t have to romanticize creative community to realize how much of an impact these efforts make on the quality and range of the writing coming out of a given place.

SMC: What do you hope readers will take away from Dissonance?

KD: Like a lot of contemporary poets, I write in a way that has been called “tabular.” Poetry often throws people off if it doesn’t proceed in a logical, efficient A > B > C order. . Readers can move forward and backward, up and down, around a book. Dissonance works not only with words but with white spaces, like a lot of music, where the interplay of sound and silence is core to the experience. There are also photographs.

In other words, reading this kind of book can be like listening to a long musical work: Patterns emerge with time, as you get to know it, gradually. I never feel like I grasp a long work of poetry or music the first time—most of it bounces off my mind. The reward builds with more exposure. So I suppose that Dissonance could grow in the mind with repeat visits, and because of that dimension of time, the takeaway will intertwine with a reader’s own thoughts, experiences, silences.

SMC: What’s next for you on the publishing front? Are you working on new poetry, a new collection?

KD: With three books just out in late 2024 and early 2025—Dissonance and two literary translations—I’m in transition. Right now, I’m working into new projects, when it’s best to hold off from saying much. In general, I tend to write more than one type of work at a time: poetry, translations, essays (usually contextualizing someone else’s work), even extended scholarly research. Moving back and forth between projects has always been productive for me and makes the results unusual.

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.