Lecture speaker looks ahead a century for Judaism

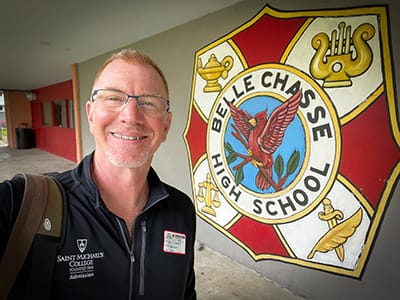

Directly above, Oppenheimer talks with Ohavi Zedek Rabbi Amy Small; photos below show the image of the late Max Wall projected on the Dion screens; a close-up of some listeners, and the rabbi and guest speaker taking questions as snow falls behind them. (all photos by Brother Thomas Berube, SSE)

“Judaism is hard,” and most authentically thrives only in community, posited Mark Oppenheimer, the popular journalist who was Thursday evening’s guest speaker for the annual Rabbi Max B. Wall Lecture at Saint Michael’s College.

Oppenheimer is a writer/speaker/teacher with a reputation for being “eclectic, insightful and prolific,” according to his introducer, Herb Kessel of the College’s economics faculty — from the guest speaker’s New York Times columns and podcasts to articles in journals ranging from The Christian Forward, Playboy to the Wall Street Journal.

Speaking to about 75 people in the Dion Family Student Center Roy Room, Oppenheimer suggested with abundant humor, warmth and passion that 100 years from now, Judaism might find itself viewed in three basic categories: first, a more orthodox and “enclaved” group that he calls the “Amish model” – “a somewhat beloved and occasionally somewhat detested American curiosity with peculiar dietary practices and working in certain professions” — they’re growing fastest with big families, he said; second, a group whose members gather socially around their Jewishness maybe six times a year for festivals, but not owning a building with a paid employee as at a synagogue – he termed this group “Contra Dance Jews” for the similar warm and liberal dynamics one experiences at those widespread secular folk-dances; and third, “those trying to do it by themselves” through reading, cultural affinity and contemplation around traditional Jewish Talmudic teaching — mainly those who are ancestrally Jewish or converts, but, “for reasons sometimes outside their control, they will not be in community.”

That third group — already today a growing sector in Judaism, particularly among the young, he said — presents a vision most troubling to Oppenheimer, since to him, “that’s not what Judaism was sent to earth with — It was sent because God didn’t want to be alone — so we help each other to model how not to be alone.”

“Only if we’re letting people exist in solitude will Judaism have really failed, since Judaism is not a religion of solitude,” he said.

Among those attending Thursday’s talk were Rabbi Amy Small of Burlington’s Ohavi Zedek Synagogue, who offered commentary after Oppenheimer’s talk and had a spirited exchange with him on points of agreement and disagreement; the daughters (with families) of Rabbi Max Wall,

To animate his point about Judaism being hard, Oppenheimer at the talk’s start described a “dream” Sabbath service experience for him – a well-trained choir, short sermon, no mention of hard spiritual things, coffee “caffeinated with cream,” friendly nametags – yet, he awakens from that dream and tells his wife “I just dreamt I went to a liberal Protestant service!” None of those “dream” things could have happened at his conservative synagogue for various reasons, he said. And it’s not just the services that can make Judaism hard, he said, but the demands – kosher food, fasting, “periodic Twitter abuse from antisemitism,” prayers in a challenging language. “Is it any wonder our numbers are in trouble?” he asked. Yet, he is heartened by traveling the U.S. to speak and feeling the warmth of the vast majority of people he meets; heartened, too, by the all-important meaningful sense of community that his tradition offers to himself and so many others.

But the “crass question of numbers” is nevertheless a concern, he said, given that at most 2 percent of the American population is Jewish — no more than 15 million Jews worldwide, and “the birth rate is below replacement.” If the health of a community can be measured demographically, “it’s one thing you want to talk about,” he said, noting that “in order to be Jewish we need other Jews” – as a basic example, for Kaddish when a Jew dies, 10 Jewish mourners are needed. But, while it is now less a given that Jews marry Jews than ever before, still, compared with other religions, “way more Jews marry Jews than Lutherans marry Lutherans,” and the rate still is probably higher than among Catholics, for instance. Also on the positive side in his view, more and more Jews are interested in serious study of traditions like the Talmud. “It would be as if for Catholics there was a worldwide Thomistic renaissance with thousands studying Aquinas – it’s extraordinary what’s going on,” he said, particularly with groups in cities. So in

Rabbi Amy Small’s main point in response seemed to be that change is something Jews have known well and welcomed all through history. “The tradition has continued to develop, be interpreted and evolved … so much has changed – when we look at the sweep of Jewish tradition and practice, what is the same?” But, “We’re still here – we’re Jews, committed to being in covenantal relationship in a community that cares about that together.” She said for those reasons, “I’m just not afraid” of some of the possible concerns Oppenheimer raised in his looking to the future 100 years hence. “We have a lot that holds us together,” Rabbi Small said. Also, the movements among younger Jews mentioned by the speaker as a concern for him since they are done in isolation, nonetheless “demonstrate a yearning and spiritual hunger” and a “craving for spiritual succor,” which is universal among humans — and “it’s right there in the tradition” for them to find. “So the tradition of engaging in relationship with God, of character, morality and ethics that lets us connect through the centuries, I think that will continue as it has,” she said. “How will that look? If you ask me, I say, “Who knows!? I won’t even guess!”

A question-answer session raised exchanges – including several emanating from questions by Edmundites, about the prophetic voice of Judaism for America on community and other issues, on the nature of covenant in seeking relationship with God, and the challenges posed by the recent popularity of DNA testing given the emphasis Judaism places on such matters of lineage traditionally. “Genetics tests may help or harm people” depending on the particulars of each case, said Oppenheimer.

Concluded Rabbi Small “The experience of being a persecuted and disempowered people drives Jews in this country to strive for something so much bigger and better than we were allowed to have in the past — and that’s what drives us now.”