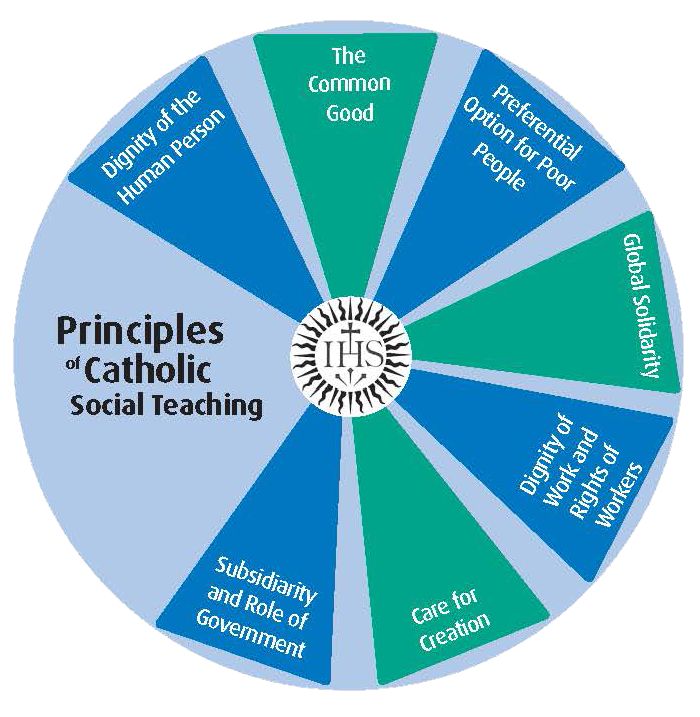

One of the most urgent and spiritually resonant themes of Catholic Social Teaching is the seventh: Care for God’s Creation. This principle, affirmed by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, reminds us that “we show our respect for the Creator by our stewardship of creation.” What may once have been viewed as a peripheral issue—often dismissed as secular environmentalism—is now recognized as central to the Catholic faith, rooted in Scripture and enriched by the evolving insights of the Church’s magisterial teaching.

One of the most urgent and spiritually resonant themes of Catholic Social Teaching is the seventh: Care for God’s Creation. This principle, affirmed by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, reminds us that “we show our respect for the Creator by our stewardship of creation.” What may once have been viewed as a peripheral issue—often dismissed as secular environmentalism—is now recognized as central to the Catholic faith, rooted in Scripture and enriched by the evolving insights of the Church’s magisterial teaching.

At its core, the call to care for creation is about more than ecological awareness or activism. It is a theological and moral imperative: the way we treat the earth reflects how we relate to its Creator and to one another, especially the poor and future generations. But to understand the full depth of this teaching, we must return to where it all began—the Book of Genesis—and examine how our interpretation of humanity’s role in creation has matured over time.

From Genesis to Greed: A Troubled Legacy

The early chapters of Genesis provide the foundational image of human beings in relation to the natural world. In Genesis 1:26–28, God creates humanity “in our image, after our likeness,” and gives them “dominion” (radah in Hebrew) over the fish of the sea, the birds of the air, and every living thing. For centuries, the word “dominion” was interpreted by many as a kind of divine sanction for human supremacy over nature, which often led to the exploitation of creation for human ends.

But this is a misunderstanding, or at least an incomplete understanding, of the Genesis narrative. The notion of “dominion” is immediately qualified by Genesis 2:15, where the human being is placed in the garden “to till it and keep it.” The Hebrew verbs here—abad (to serve) and shamar (to guard or preserve)—imply responsibility, humility, and reverence. The human task is not one of domination in the modern industrial sense, but of caretaking, tending the earth as one might tend a sacred trust.

But this is a misunderstanding, or at least an incomplete understanding, of the Genesis narrative. The notion of “dominion” is immediately qualified by Genesis 2:15, where the human being is placed in the garden “to till it and keep it.” The Hebrew verbs here—abad (to serve) and shamar (to guard or preserve)—imply responsibility, humility, and reverence. The human task is not one of domination in the modern industrial sense, but of caretaking, tending the earth as one might tend a sacred trust.

This insight, long buried beneath centuries of anthropocentric theology and economic expansionism, is now being recovered and emphasized by theologians, Scripture scholars, and popes alike. The biblical mandate is not to exploit the world but to safeguard it, ensuring that the goods of creation are shared equitably and sustained for generations to come.

Papal Teaching: A Developing Tradition

The modern Catholic concern for the environment began to take shape in the aftermath of industrialization and global conflict. In Rerum Novarum (1891), Pope Leo XIII addressed the rights and duties of labor and capital but already hinted at the ethical implications of economic systems for social and material well-being. Environmental themes, however, remained in the background until the second half of the 20th century.

Pope John Paul II brought a deeper ecological awareness into focus. In his 1990 World Day of Peace Message, he declared that “the ecological crisis is a moral issue” (Peace with God the Creator, Peace with All Creation, 15). He emphasized that respect for life extends beyond human life to all of creation and warned against consumer attitudes and lifestyles that threaten the natural world (ibid., 13).

Benedict XVI, often called “the green pope,” expanded on this foundation. In Caritas in Veritate (2009), he wrote, “The environment is God’s gift to everyone, and in our use of it we have a responsibility towards the poor, towards future generations and towards humanity as a whole” (48). For Benedict, ecological concern was inseparable from the Church’s teaching on justice, solidarity, and the common good.

Benedict XVI, often called “the green pope,” expanded on this foundation. In Caritas in Veritate (2009), he wrote, “The environment is God’s gift to everyone, and in our use of it we have a responsibility towards the poor, towards future generations and towards humanity as a whole” (48). For Benedict, ecological concern was inseparable from the Church’s teaching on justice, solidarity, and the common good.

This trajectory of thought reaches a new level of urgency and integration with Pope Francis. Though Laudato Si’ (2015) deserves its own full treatment, it is worth noting here that Francis shifts the conversation decisively away from dominion and toward relationship. He reframes the human vocation not as ruler of the earth but as part of a “communion of all creation”—a mutual and interdependent whole (Daniel P. Scheid, “The Communion of Creation: From John Paul II and Benedict to Francis,” America: The Jesuit Review, June 18, 2015). Creation, in his view, is not a resource to be used but a “book” to be read, a “sister” to be loved, and a “common home” to be protected (cf. 1, 2, 11, 19, and 233; Pope Benedict XVI, Caritas in Veritate, 2009, 51).

A Change of Heart, A Change of Mind

This evolving understanding reflects not only deeper scriptural exegesis but also a conversion of imagination. To be a steward of creation in the 21st century means recognizing that the earth’s ecosystems are fragile, interconnected, and vulnerable to human choices. It means hearing “both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor” as one and the same cry (Pope Francis, Laudato Si’, 15). The devastation of the environment disproportionately harms the marginalized, particularly those in developing nations and low-income communities who suffer from polluted air, contaminated water, and climate instability.

In this light, “care for God’s creation” is not a side concern; it is a test of our faithfulness to the Creator. Just as we cannot claim to love God while ignoring the suffering of our neighbors, we cannot claim to honor God while degrading His handiwork. The Catholic tradition, informed by centuries of theological reflection, now sees environmental degradation as a sin against both creation and the Creator—a violation of justice, prudence, and charity.

Living the Teaching

What does this mean for us today? It means we must examine our habits of consumption, waste, and indifference. It means parishes, schools, and Catholic institutions must take practical steps toward sustainability: conserving energy, reducing emissions, supporting local agriculture, and advocating for environmental justice. It means raising our voices in public discourse, not just as citizens, but as people of faith who see the planet as sacred ground.

What does this mean for us today? It means we must examine our habits of consumption, waste, and indifference. It means parishes, schools, and Catholic institutions must take practical steps toward sustainability: conserving energy, reducing emissions, supporting local agriculture, and advocating for environmental justice. It means raising our voices in public discourse, not just as citizens, but as people of faith who see the planet as sacred ground.

It also means cultivating wonder, gratitude, and humility—rediscovering creation as a gift that reveals the Creator. In a world often driven by utility and profit, such reverence is itself a radical witness.

The full implications of Laudato Si’ and Pope Francis’s vision will be the subject of a future blog. For now, it is enough to recognize that the Church is calling us to a new understanding of our place in creation: not as masters, but as servants of life. The seventh theme of Catholic Social Teaching is a summons to return to the garden, not to dominate but to serve and protect, to till and to keep, as God intended from the beginning. In doing so, we not only heal the earth, but also our relationship with the One who made it.

If you would like to make a comment or ask a question, I can be reached at dtheroux@smcvt.edu. Let’s talk!

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.