A Line Too Low: Rethinking Poverty and Just Wages in Light of Catholic Social Teaching

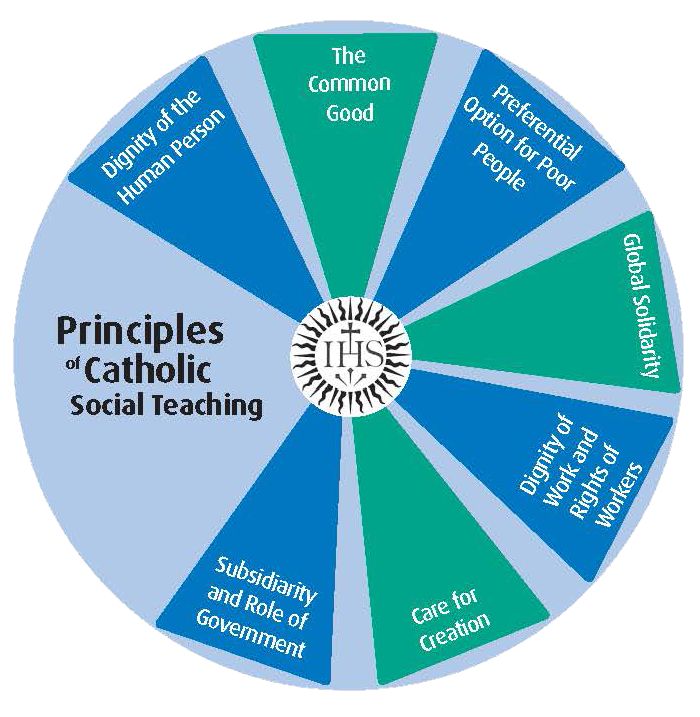

At Saint Michael’s College, rooted in the tradition of the Society of Saint Edmund, we take seriously the call to build a more just and compassionate society. This call is more than idealism. It is a commitment grounded in the Gospel and in Catholic Social Teaching, which holds up the dignity of work and the rights of workers as one of its central principles. And yet, in our daily conversations about poverty, need, and assistance, we often rely on an all too familiar but inadequate tool: the federal poverty line.

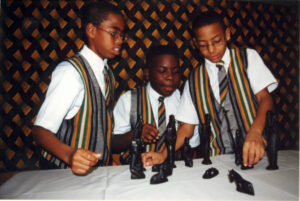

During my years as principal of a tuition-free middle school for African American boys in New Orleans, we used the poverty line to determine financial eligibility to attend a school intended for young men caught in poverty. In addition, it was a practical guide, used to qualify students for free or reduced-price meals. But even then, I recognized its limitations. Developed in the 1960s, based on food costs and only adjusted for inflation, the federal poverty line does not account for the dramatic rise in costs for housing, healthcare, childcare, or transportation. Nor does it reflect the reality that these costs vary greatly by region. Vermont, for example, has higher housing and heating costs than many states, but the same poverty line is applied across the country.

During my years as principal of a tuition-free middle school for African American boys in New Orleans, we used the poverty line to determine financial eligibility to attend a school intended for young men caught in poverty. In addition, it was a practical guide, used to qualify students for free or reduced-price meals. But even then, I recognized its limitations. Developed in the 1960s, based on food costs and only adjusted for inflation, the federal poverty line does not account for the dramatic rise in costs for housing, healthcare, childcare, or transportation. Nor does it reflect the reality that these costs vary greatly by region. Vermont, for example, has higher housing and heating costs than many states, but the same poverty line is applied across the country.

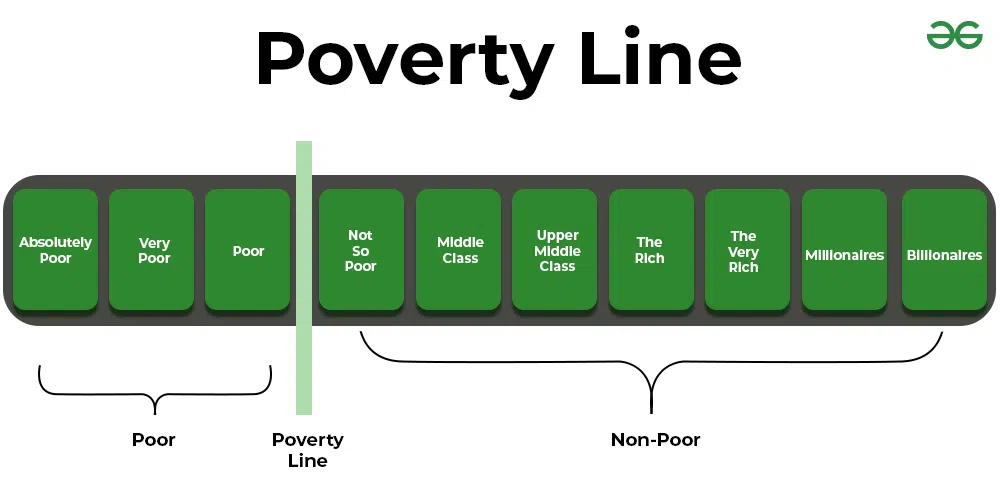

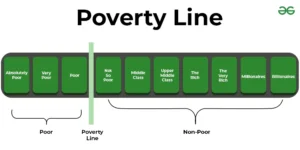

Even many families earning above the poverty line still cannot afford basic needs, and this line, though convenient for policy purposes, fails to measure what is required for a life of dignity. It defines poverty in terms of survival, not in terms of social participation or human flourishing. That gap between statistical poverty and real-life hardship is where the Church’s wisdom becomes urgent.

In Rerum Novarum (1891), Pope Leo XIII addressed this issue directly:

“Let it be taken for granted, therefore, that remuneration for labor must be enough to support the wage‑earner in reasonable and frugal comfort. If, through necessity or fear of a worse evil, the workman accepts harder conditions because an employer or contractor will afford him no better, he is made the victim of force and injustice.” (Rerum Novarum, §45)

This foundational teaching insists that wages must support a life of dignity, not merely subsistence. A just wage is not determined solely by what the market can bear or what an employer is willing to pay. It is measured by what is necessary for a person and their family to live securely and participate fully in society. Yet today, a person working full-time at minimum wage in Vermont, or nearly any other state, often cannot afford safe housing, healthcare, or childcare.

The Society of Saint Edmund understood this truth not only in theory but in practice. In the 1930s, the Edmundites extended their ministry to Selma, Alabama, and the surrounding rural areas, where Black sharecroppers and their families lived under generations of economic and racial oppression. The Edmundite Southern Missions began not simply by offering charity but also by standing in solidarity with the poor: creating schools, advocating for civil rights, providing food and clothing, and insisting that dignity required more than survival.

Their commitment continues today as Edmundites work to support Black farmers, promote food security, and walk with those who are economically marginalized. They embody the Church’s belief, rooted in the dignity of the human person, that no one should be left behind because the “official” poverty line does not reflect the true cost of living.

Their commitment continues today as Edmundites work to support Black farmers, promote food security, and walk with those who are economically marginalized. They embody the Church’s belief, rooted in the dignity of the human person, that no one should be left behind because the “official” poverty line does not reflect the true cost of living.

The U.S. bishops echo this in their 1986 pastoral letter Economic Justice for All:

“Every person has a right to life and to the material necessities that are required to sustain it: food, shelter, clothing, health care, education, and employment.” (§80)

“Wages must honor the dignity and worth of the person. They must be at least sufficient to provide adequately for the needs of the worker and his or her family.” (§103)

Here in Vermont, where rural poverty, housing costs, and underemployment often go unrecognized, this teaching matters. And it matters to us as a Catholic college community of educators, staff, students, and alumni who prepare students for vocations in which the dignity of every person is a starting point for action. We are called to imagine something more than a poverty line; we are called to imagine a living wage. A wage that allows people not only to survive but to grow, to rest, to raise children, to contribute, to hope. This is not simply an economic issue; it is a moral one. As Pope Francis reminds us in Laudato Si’:

“Business is a noble vocation, directed to producing wealth and improving our world. It can be a fruitful source of prosperity for the areas in which it operates, especially if it sees the creation of jobs as an essential part of its service to the common good….The broader objective should always be to allow other peoples a dignified life through work. A just wage enables them to have adequate access to all the other goods which are destined for our common use.” (Laudato Si’, 128 and 129)

enables them to have adequate access to all the other goods which are destined for our common use.” (Laudato Si’, 128 and 129)

It is important for us, as members of a Catholic and Edmundite college, to engage deeply with questions of justice and economic dignity. Minimal thresholds like the federal poverty line should not be mistaken for moral standards. It is important for us to recognize the difference between policy tools and ethical imperatives, and to insist that public discourse and institutional practice reflect the full dignity of the human person. In continuing the legacy of the Edmundites, who have stood with the poor in both the North and the South, it is important for us to examine how economic systems measure human worth, and to challenge those that fall short of justice.

If you would like to comment or ask a question, I can be reached at dtheroux@smcvt.edu. Let’s talk!

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.