No one at St. Mike’s knows the flow cytometer quite like Olivia Goldfarb ’27. She was the first to use the specialized laboratory equipment when the College acquired one a year ago through a grant, and she has logged the most hours on it so far.

Biology Professor Lyndsay Avery explained that at most other colleges – including large research institutions – an undergraduate like Goldfarb would not be able to use a flow cytometer, which uses lasers, fluid, and fluorescent dyes to identify certain characteristics of single cells.

This summer, Goldfarb has been using the equipment to examine cell division of T cells with and without the mutation that causes X-MAID, a rare immunodeficiency disease. She and fellow summer researcher, Gavin Graham ’25, are attempting to understand what is happening at the cellular level to potentially help patients who suffer with this life-shortening condition.

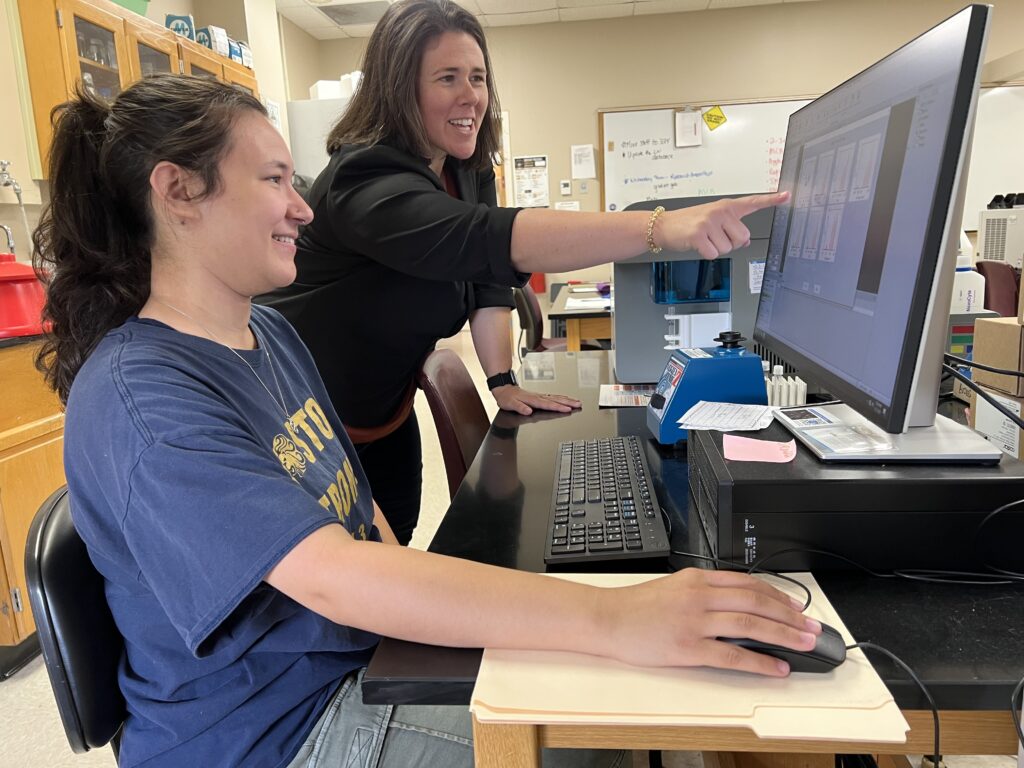

Olivia Goldfarb ’27 (left) runs a report from the flow cytometer to pinpoint specific properties within cells while Biology Professor Lyndsay Avery points at data. For her summer research project, Goldfarb built upon Avery’s work which seeks to understand the cellular differences that contribute to X-MAID, a rare immunodeficiency. (Photo by April Barton)

Building upon years of research into one disease

For their summer research projects, Graham and Goldfarb continued work they were doing last summer and through the school year, which builds upon years of research from Avery and former and current St. Mike’s students working to understand x-linked moesin associated immunodeficiency, or X-MAID.

In X-MAID patients, the T cells, which normally travel throughout the body to the site of an infection, have lost their mobility due to a mutation of the protein moesin. Without the ability of T cells to travel to an infection within the body, the person experiences frequent illnesses and difficulty fighting off infection.

The rare disease was first identified in 2012, though modern genetic testing proves that it has affected generations of families. The disease only occurs in males; women are carriers of the mutation on one of their x chromosomes. X-MAID is often discovered during routine infant testing at birth.

Avery’s interest in the disease started in 2018, when she began post-doctoral research into it, which has continued through her and her students’ work at St. Mike’s.

In fact, Saint Michael’s College is one of the few labs studying this disease. Several experts on this particular protein recently retired and others who are studying X-MAID are clinicians and not doing the same type of in-depth cellular level research, according to Avery. Around 18 cases of X-MAID have been confirmed so far, and while that may not seem like a lot, St. Mike’s is able to offer hope to those families managing the disease.

“You’re not going to see Pharma doing research on this because it’s not going to pay out,” Avery said.

Results of experimentation

Gavin Graham ’25 shows off solution being incubated in the lab during summer 2025 that helps him and other researchers understand the properties of X-MAID, a rare immunodeficiency. (Photo by April Barton)

To treat X-MAID, patients often undergo a bone marrow transplant or recurring transfusions which can be risky and traumatic, especially for young kids. In one instance, a patient died from complications following a bone marrow transplant.

To create more effective and targeted treatment, more needs to be known about what is happening at the cellular level. Goldfarb’s summer research tested whether cell division might be affected by the X-MAID mutation – analyzing normal T cells and those with the mutation. Graham went even smaller, at the protein level, looking at natural moesin and mutated moesin and its binding partners.

“I think it’s either binding something it’s not supposed to or it’s not binding what it needs to to be activated correctly and to have proper function,” Graham posited.

Last summer, he designed a way to isolate moesin and refined the process throughout the school year. For this summer’s research project, he used a technique called immunoprecipitation to gather both regular moesin and mutated moesin, as well as their binding partners. He sent those samples to the proteomics lab at the University of Vermont to run spectral counting on the 300-ish bound proteins. One protein – ACAP1 – stood out as having the greatest difference between the regular moesin and the negative control versus the mutated moesin. In the mutation, the scarcity of ACAP1 was significant.

Olivia Goldfarb ’27 changes the fluids of the flow cytometer, a specialized piece of lab equipment, which was central to her summer research project. The equipment allowed Goldfarb to test regular and mutated T cells with X-MAID, a rare immunodeficiency, for differences that could contribute to the disease. (Photo by April Barton)

Graham doesn’t feel this is enough data yet to make a reliable conclusion. Ideally, he would have liked to perform three screens and planned for more. However, federal funding through Vermont Biomedical Research Network ran out and had yet to be reinstated. This coincided with cuts and halts to other federally funded scientific research across the nation this spring and summer.

For now, Graham is reading up on and testing this particular protein, about which not much is known other than that it contributes to cell mobility. It’s possible this is a discovery that could yield more information about the disease.

Goldfarb’s results, on the other hand, showed that cell division didn’t seem to be materially different between the normal T cells and mutated ones.

Before the summer, Goldfarb developed a way to synchronize cells to undergo cell division, or mitosis, at the same rate and stage in order to more easily compare them. Through testing this summer, she found no difference in mitosis, but her work was still a step forward.

This was something that research had not shown before, Goldfarb said.

“Having just that little bit of confirmation is validating to know that some things are different with the mutated cells and some things are the same,” Goldfarb said. “How do they behave similarly is just as important as figuring out how they behave differently.”

How research not only impacts their future, but possibly others’ futures

The research St. Mike’s students are doing could have implications for those living with X-MAID or other immunodeficiencies.

Moesin is just one actin-binding protein that causes immunodeficiency, Avery said, adding that there are other similar diseases their research might be able to help – like Wiskott-Aldrich, which has as many as 5,000 people living with the disease.

Both Graham and Goldfarb anticipate having careers that involve scientific research and feel fortunate to have had this experience early on in their education during their undergraduate years to help solidify their next steps.

Goldfarb switched her major to Health Science – away from Biology and a physician-focused track – in part because of her affinity for research. She hopes to find a way to incorporate research and some patient care in a job that allows her to do both.

Gavin Graham ’25 studies cells under the microscope for summer research project involving X-MAID, a rare, immunodeficiency disease. (Photo by April Barton)

Graham, a Biochemistry major on track to graduate in December, is weighing his options for graduate school. He is considering studying abroad because the European Union is offering U.S. students opportunities and funding that have diminished lately domestically.

“Research has been instrumental in my college career especially with figuring out what I want to do afterwards – opening me up to so many different possibilities,” he said. “It’s given me so much knowledge about how things work in science, in general, and I feel like I definitely have a leg up compared with peers when we read a scientific paper or talk about something in class.”

Avery relishes her role training up young scientific researchers; it’s her favorite part of the job.

“They’re going to go on to do much greater, more amazing, pertinent science than I will here,” she said. “My goal is to create the next generation of scientists – that maybe would not have gotten an opportunity someplace else.”

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.