From its very beginning, Christianity has affirmed a startling truth: the eternal Word of God became flesh, not in some generic human form, but in the marked, particular body of Jesus of Nazareth. This is the meaning of the Incarnation. As M. Shawn Copeland reminds us in her chapter essay “Marking the Body of Christ,” Jesus was a poor, Jewish man in a colonized land (The Meaning of Being Human: Synodal Considerations, 2025, 29-35). His life, death, and resurrection proclaim the sacred value of all human bodies, each one unique, marked by history, gender, race, culture, and experience.

From its very beginning, Christianity has affirmed a startling truth: the eternal Word of God became flesh, not in some generic human form, but in the marked, particular body of Jesus of Nazareth. This is the meaning of the Incarnation. As M. Shawn Copeland reminds us in her chapter essay “Marking the Body of Christ,” Jesus was a poor, Jewish man in a colonized land (The Meaning of Being Human: Synodal Considerations, 2025, 29-35). His life, death, and resurrection proclaim the sacred value of all human bodies, each one unique, marked by history, gender, race, culture, and experience.

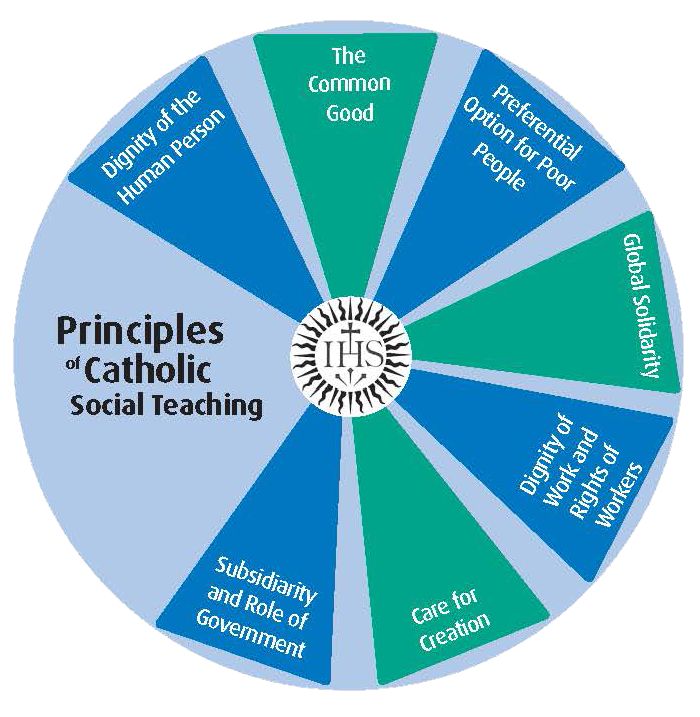

This insight is at the heart of Catholic Social Teaching. The Catholic Church insists on the dignity of every person, created in the image of God. But we cannot affirm that dignity in the abstract, as if people exist as “universals” that are the same everywhere. A celebration of the dignity of each person must be lived out in our solidarity with real people whose bodies carry visible and invisible marks, the scars of racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, poverty, or exclusion. To ignore those realities is to risk what Copeland calls a “false universality,” a neutrality that can only privilege the powerful while silencing the marginalized.

Catholic Social Teaching and the Marked Body

Catholic Social Teaching outlines principles that direct us toward a just society: the dignity of the human person, the call to community and participation, the option for the poor, the dignity of work, solidarity, and care for creation (United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, “Seven Themes of Catholic Social Teaching, usccb.org). Copeland deepens these principles by insisting that our theology must take seriously the particularity of bodies (31).

To speak of human dignity without naming the forces that degrade certain bodies is to offer half the truth. When we speak of solidarity without recognizing those whose bodies are systematically excluded, we utter hollow words. The crucified and risen body of Jesus makes clear that God’s love embraces all our “marked bodies” — Black and brown bodies, women’s bodies, LGBTQ+ bodies, disabled bodies, migrant bodies, aging bodies (32). None are erased; all are re-valued in Christ (33).

Why DEI Matters

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives are practical efforts to put these truths into action. At their best, DEI programs do three essential things:

- Affirm diversity by recognizing the uniqueness of every person.

- Pursue equity by challenging systems that privilege some while excluding others.

- Foster inclusion by ensuring that all people have a real voice and place in community life.

In a Catholic context, DEI is not an add-on to the mission. It is a direct expression of Catholic Social Teaching. DEI acknowledges that bodies are not treated equally in society and seeks to create conditions where dignity, solidarity, and participation can flourish. It mirrors the Church’s “option for the poor and vulnerable” by centering those most often pushed to the margins.

The U.S. Debate Over DEI

Today, in schools, corporations, and government agencies, there is a growing movement to eliminate references to DEI. Advocates of this rollback often argue that everyone should be treated “the same.” But Copeland’s work shows why this claim is deeply problematic.

Treating everyone “the same” ignores how history has marked bodies differently. It denies the reality of racism, sexism, and other exclusions that shape people’s daily lives. Far from being neutral, such erasure reinforces the dominance of those already privileged. It is, in Copeland’s terms, a refusal to acknowledge the scandal of the Cross, that God chose to enter human history through a poor, Jewish, colonized body (33).

Faithful Resistance

Theologically, to abandon DEI is to turn away from the Incarnation of Jesus. If God embraced the particularity of a human body in the person of Jesus, then we cannot ignore or dismiss the particularities of each other. Socially, to abandon DEI is to risk a society where only some bodies are safe, welcome, or free to flourish.

Catholic colleges, parishes, and institutions must resist this narrowing of vision. Preserving DEI is a way of being faithful to Christ and his Body, the Church. It is a way of proclaiming that our differences are not obstacles to community but essential to its richness.

Copeland concludes that the body of Christ “is the only body capable of taking us all in as we are with all our different body marks” (32). DEI work, in tandem with Catholic Social Teaching, helps make that truth visible in classrooms, workplaces, and communities. To let go of DEI would not only betray vulnerable people; it would betray the Gospel itself and God’s choice to become like us in all things but sin (Hebrews 2:17).

If you would like to make a comment or ask a question, I can be reached at dtheroux@smcvt.edu. Let’s talk!

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.