Viewpoint Diversity, Social Justice, and DEI: A Catholic College’s Way Forward Part I

“Viewpoint diversity” has moved from campus debate to public policy. As Inside Higher Ed reported on September 2, 2025, federal officials and conservative legislators are pressing universities to demonstrate “viewpoint diversity,” sometimes with threats to condition funds on ideological audits and the creation of civics or Western civilization centers (Ryan Quinn, “The Battle for ‘Viewpoint Diversity,’” Inside Higher Ed, Sept. 2, 2025). For a Catholic college, the question is not whether a range of ideas should be welcome. The question is how to widen intellectual range without surrendering research objectivity or Catholic commitments to social justice, and how to situate diversity, equity, and inclusion within that Catholic frame.

What objectivity actually requires.

What objectivity actually requires.

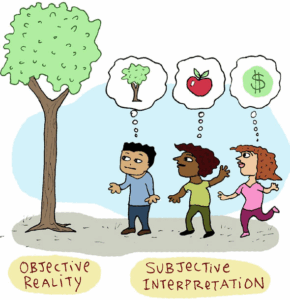

Objectivity in scholarship is not a partisan headcount. It is a set of practices that make claims testable, criticizable, and transparent. The National Academies summarize research integrity in terms of objectivity, honesty, openness, fairness, accountability, and stewardship, and they urge institutions to embed these values across the research life cycle (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Fostering Integrity in Research, Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2017). Open-science practices such as preregistration where appropriate, data and code sharing, and clear conflict-of-interest disclosures operationalize those values without importing ideological quotas into hiring or peer review (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Open Science by Design: Realizing a Vision for 21st Century Research, Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2018). Classic sociology of science makes the same point. Robert K. Merton’s norms of universalism, communalism, disinterestedness, and organized skepticism protect inquiry from partisanship by anchoring it in method and evidence (Robert K. Merton, “The Normative Structure of Science,” in The Sociology of Science: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations, ed. Norman W. Storer, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973).

When “viewpoint diversity” helps, and when it harms.

A constructive reading of “viewpoint diversity” centers on epistemic and methodological diversity. Inviting serious competing hypotheses and traditions into the same room reduces blind spots and groupthink. There is growing empirical evidence that diverse teams often produce more highly cited and innovative work. For example, large-scale analyses of millions of papers  find strong positive associations between ethnic diversity in teams and citation impact (Bedoor K. AlShebli, Talal Rahwan, and Wei Lee Woon, “The Preeminence of Ethnic Diversity in Scientific Collaboration,” Nature Communications 9, no. 5163, 2018; Richard B. Freeman and Wei Huang, “Collaborating with People Like Me: Ethnic Coauthorship within the United States,” Journal of Labor Economics 33, S1, 2015). Other studies point to advantages for gender-diverse teams in novelty and impact (Heather B. Love et al., “Gender-diverse teams produce more novel, higher-impact scientific ideas,” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 9, 2022).

find strong positive associations between ethnic diversity in teams and citation impact (Bedoor K. AlShebli, Talal Rahwan, and Wei Lee Woon, “The Preeminence of Ethnic Diversity in Scientific Collaboration,” Nature Communications 9, no. 5163, 2018; Richard B. Freeman and Wei Huang, “Collaborating with People Like Me: Ethnic Coauthorship within the United States,” Journal of Labor Economics 33, S1, 2015). Other studies point to advantages for gender-diverse teams in novelty and impact (Heather B. Love et al., “Gender-diverse teams produce more novel, higher-impact scientific ideas,” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 9, 2022).

Harm arises when political actors attempt to mandate viewpoint balance by numbers or tie funding to ideological audits. The American Association of University Professors warns that sweeping “neutrality” rules can chill inquiry and that academic freedom and shared governance remain the best guards for research integrity (AAUP, On Institutional Neutrality, adopted Jan. 2025). Many institutions pair that stance with strong free-expression commitments like the University of Chicago’s 2015 statement, which defends wide-open debate while distinguishing institutional partisanship from protecting debate itself (University of Chicago, Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression, 2015). The 1967 Kalven Report further cautions that a university must sustain “the conditions for freedom of inquiry,” which can be compromised when the institution speaks in ways that foreclose debate (Kalven Committee, Report on the University’s Role in Political and Social Action, 1967).

Report on the University’s Role in Political and Social Action, 1967).

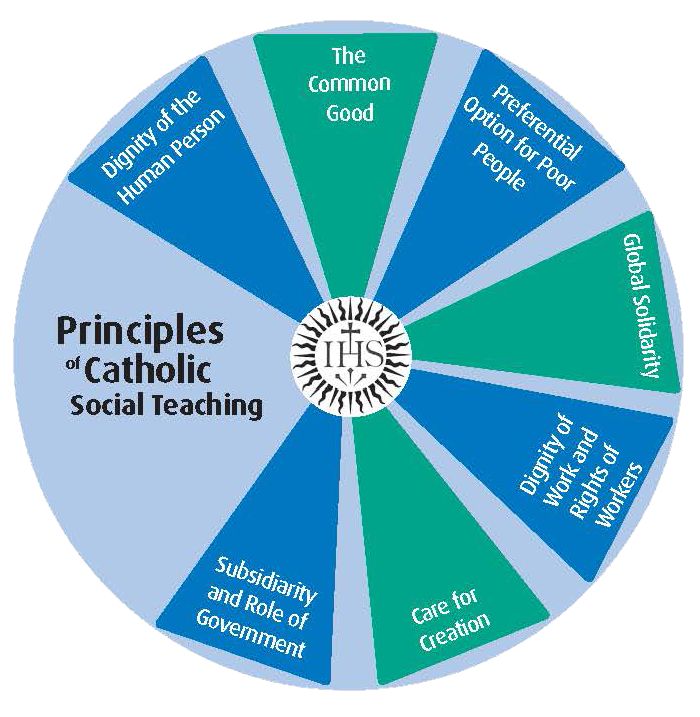

For Catholic higher education, then, the challenge is not only to resist simplistic quotas in the name of “viewpoint diversity” but also to frame intellectual life within a deeper moral vision. Research integrity, free inquiry, and shared governance safeguard objectivity, but Catholic identity adds a further horizon: the pursuit of truth ordered to human dignity and the common good. This is where the principles of Catholic Social Teaching meet the contemporary debates around diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

The next reflection will turn directly to that question—how DEI, seen through a Catholic lens, can deepen rather than diminish the university’s mission.

If you would like to make a comment or ask a question, I can be reached at dtheroux@smcvt.edu. Let’s talk!

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.