Students brave snow, cold for science

Contrary to logical perception, it’s possible to collect plenty of living insects for science study in early February’s freezing cold and snow within walking distance of a Saint Michael’s College biology lab. It just takes snow shoes for everyone, an adventuresome professor like Biology Department Chair Declan McCabe as a guide — and a whole lot of gall(s).

“Gall” describes a quarter-sized protective cyst that forms around fly larvae laid in goldenrod by a species called the goldenrod gall fly. Female flies lay eggs into the growing tip of the goldenrod, which just happens to grow bounteously in warmer months around the old Saint Michael’s organic garden and the new Solar Array. Both are along the road down the hill by the Merrill Cemetery alongside the jug-handle that’s across Route 15 from campus..

It’s an area where the goldenrod’s stalky remnants protrude still from the snow all winter. Chemicals released by the hatchling larva cause the plant to form a corky spherical “gall” about the diameter of a quarter, McCabe says. The larva spends about 50 weeks in the gall feeding on plant tissue, growing, and pupating, before emerging as an adult to complete the life cycle.

This provides him and his students “the perfect way to study a plant, its herbivore, and the predators of the herbivore — birds, which eat them, or adult beetles and wasps which lay their own eggs in the galls, and the hatched larvae consume the fly larvae before emerging as adult beetles and wasps). It’s three trophic layers of a system,” examinable in a single class session or perhaps two. A big plus too is that samples can be collected for free and close-by, he says.

For three years in a row now students in his evolution class have collected a sample of about 250 galls during the first week of class in mid-January – but this year they were a little later due to weather. It’s the second year in a row they’ve used snow shoes made available through the college’s vibrant Wilderness Program. “It makes it a much better lab,” McCabe says. “Two years back we did it in boots on light snow and icy patches and it was uncomfortable and slow.”

Once back in the lab with collected specimens, he said, “We will number and then measure the diameter of each gall using a plastic artist’s templates designed for drawing circles of increasing diameters. Next we carefully split the galls using pruning shears and use another scientist’s online key to determine the outcome of the gall fly’s efforts,” McCabe explained. “I would say that the pruning shears are perhaps the most important tool for success with this research project; asking 15 or 20 students to cut hard spherical objects using knives might be a recipe for disaster. As much as I respect and admire the work of the Saint Michael’s College Rescue Crew, I’d rather not set myself up to need their services.”

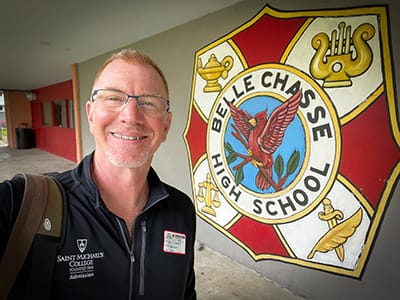

On Feb 5 about 15 students and McCabe walked or ran through the snow with baggies, collecting galls as they fanned out to pre-assigned areas on a map. Students originally from as diverse locations as New Jersey, Maryland, Ohio, Brazil and Tanzania along with many New Englanders appreciated the newness of the snowshoe experience. “It’s part of the whole experience here at Saint Michael’s,” McCabe said. “Some students are old pros and very willing to help the snow shoe novices.” One woman discovered she had picked up burrs stuck to her clothing and asked if anyone had tweezers. The class will follow up with what they collected in the lab next week.

McCabe said he borrowed the idea from a fellow scientist, Warren G. Abrahamson, of Bucknell University, who generously shared all the information needed for such a productive winter outdoor lab experience. Students in McCabe’s fall course, Community Ecology, collect aquatic insects in Lake Champlain or local rivers, using an iPhone app that he and some students helped develop to aid search and identification.

Gall fly larvae represent a high-protein meal when most other insects are underground, McCabe said, and a number of predators and parasitoids take advantage of the bounty. Woodpeckers, chickadees, beetles, and wasps all partake in the fly larva feast. “In our most recent foray into the world of gall fly biology last year, we observed that already by January, 70 percent of the galls no longer housed gall fly larvae.”

He said the data set resulting from the activity “is perfectly amenable to graphing using histograms and statistical analysis.” He said some larvae that sat in his car in a paper cup all day when the temperature dipped below freezing stayed “as soft and squishy as when they were removed from the galls – a nice illustration of the antifreeze properties of the larval tissue.”

The class will revisit the gall fly population on campus late in the semester, to see if additional months of exposure to bird predation further reduce the proportion of surviving flies, McCabe said.