Activist expats raise voices on China rights crackdown

The prominent exiled human rights lawyer Teng Biao and Saint Michael’s history Professor Rowena He told a packed hall at the College Wednesday that China currently is experiencing the worst human rights crackdown in the 28 years since the Tiananmen Massacre.

At Professor He’s invitation, Teng Biao visited campus late afternoon in the Dion Family Student Center Roy Room, where hundreds of students and faculty heard him and the professor recount their own experiences as well as those of China’s human rights lawyers and activists. They told story after story of arrests, kidnaps, torture and exile or worse for their friends, countrymen and others who dare to speak truth to power and fight for justice for the powerless.

Rowena He surveyed the large crowd and said it was “beautiful” to see once more that “we are a community of faith committed to truth and justice … You do not come because the speaker has power or money. We are here because of our shared values in rights and justice. You are here because you care.”

Rowena He started by telling about a Harvard conference in 2011. Of the five cases she presented on human rights lawyers and activists then, three had been imprisoned, and one — the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo — died as a political prisoner. Teng was the only one among the five who is free to speak in exile.

With quiet matter-of-fact intensity, both speakers talked from a table together in conversational dialogue, describing the oppression they and others have suffered. Teng said those secret police kidnappers threatened to bury him alive based on his taking on of human rights cases, before he showed credentials from universities –and later, when his family was not allowed to follow him for a U.S. university appointment, his wife and daughters had to find their way out of China through a harrowing smuggler’s route across several nations.

As members of the same generation, both Rowena He and Teng Biao considered the ongoing “rights defenders” movement in China as a continuity of the struggles of the Tiananmen Movement. Despite continuous repression and intimidation, they see it a moral imperative to get the silenced voices heard. When responding to a student question about what they could do, she said, “You have the power of the powerless. You can support by keeping yourself informed and help spread the message. Injustice somewhere is a threat to justice everywhere. Don’t wait until no one can speak up for you.”

Rowena He explained the title of the day’s program – “No country for justice” — using personal narratives of the Cultural Revolution, the Tiananmen Generation, and the new generation of Teng Biao’s daughter. “For three generations, we still do not have the basic rights that you are born with … and [Teng Biao] was disbarred and then exiled when he tried to seek justice in his own country,” she said.

Teng shared some of his personal background: coming from a poor family of farmers to Peking University in 1991, “totally brainwashed” at the time by propaganda, like most Chinese – but it was the first time he heard the words “think independently” from some brave professors. “For me, this sentence meant so much for me in China,” he said.

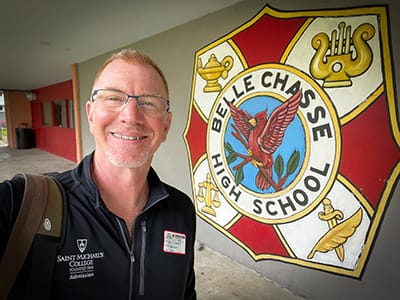

Rowena He said that 1989 was the turning point for her personal life that led to her decision in the late 1990s to cut short a promising banking career in China to leave with two suitcases for Canada and eventual studies for advanced degrees that led to Harvard and then Saint Michael’s. “It was that moment in 1989,” she said, “and in the last 28 years we have been trying to show that something in this world that that cannot be crushed by guns and tanks. That is the human spirit and the human desire for freedom and rights.”

Teng told the audience how he and a group of other lawyers founded the “Open Constitution Initiatives” in about 2003, also in the “spirit of Tiananmen.” Teng described China’s “household registration system” that denies people basic rights in any town or city other than where they are from – so they are “second class citizens.” Some of his rights cases early on related to injustices from this system, he said.

Teng also described how China’s strict “one-child policy” forced millions to undergo forced abortions or sterilization, and in his law practice, he tried to help some of those people in various ways. Others he tried to help included those denied religious liberties, such as the Falun Gong or Tibetans — or Christian churches, which are seeing more oppression recently, Teng and Professor He both said, with crosses forcibly being removed from churches; also, pastors still are sentenced to long prison terms, as has been true for some time.

Lawyers who try to stand up for any of these groups now are also being jailed, they said. Many are “disappeared,” and families have no idea where they are, as had happened for a time to Teng years ago, when he was beaten and held in brutal isolation, all without warrants. Many lawyers make statements before they go to jail now, saying not to believe false reports that they killed themselves; often, they are forced to make statements on TV, against their will — “televised confessions” — or are severely tortured. International attention will help, the speakers said.

Even outside of China, the arm of the Communist regime’s intimidation tactics sometimes can be felt, the speakers said – such as through so-called “Confucius Institutes” on college campuses that offer big money to universities but then insist on the “party line” being delivered in programs on any number of issues, compromising truth and academic integrity.

In a question and answer session, an audience member asked if they saw any risk of China’s top leader Xi Jinping declaring himself president for life. Teng said while it’s hard to say, the traditional “collective dictatorship” of the Communist Party is now more a “personal dictatorship, recycling Cultural Revolution policies like a cult of personality, so he will strengthen power, and the crackdown on civil society will continue.”

Another questioner wondered how people in China, such as his younger self, came to realize they were being lied to and denied rights. Teng answered, “In reality, people can see what’s happening,” despite what they are told – as they can’t help but witness such things as forced demolition of houses without compensation in their families or neighborhoods, or arrest and torture of family members and friends. “Some learn the idea of democracy translated from foreign languages,” he said. “It’s strictly censored, but there is some space where people can know some things the government doesn’t want them to know.”

“The human rights of all people are connected,” said Teng.