Speaker says that St. Edmund’s example matters today for leaders, faithful

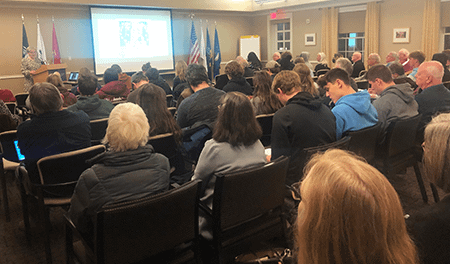

English medieval scholar Cate Gunn, PhD, holds attention of nearly 60 in Pomerleau Conference Room Tuesday for annual lecture

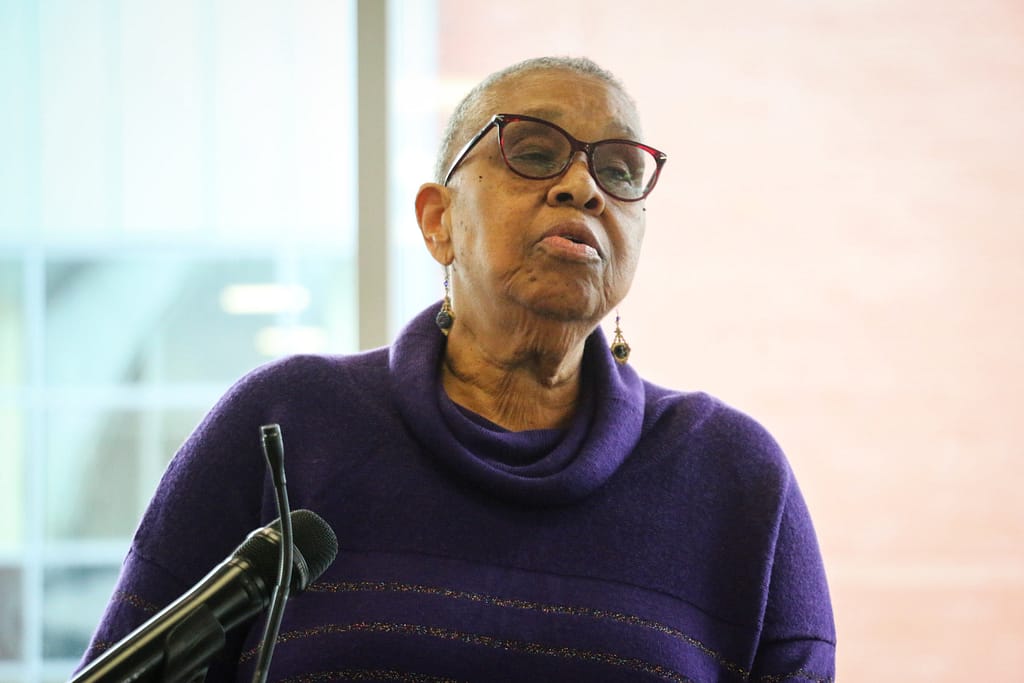

Cate Gunn, PhD, delivers the annual St. Edmund Lecture Tuesday in the packed Pomerleau Conference. Enlarged photo at bottom shows a closer view of the speaker. (Photos Lauren Read)

This year’s annual Saint Edmund Lecture began with the featured speaker, English medieval scholar Cate Gunn, wondering rhetorically why the namesake of Saint Michael’s College’s founding religious order, St. Edmund of Abingdon, should matter to us today.

The speaker then used her winning humor, animated story-telling, incisive scholarship and absorbing digressions to bring the engaged crowd of nearly 60 people packing the Pomerleau Conference Room along with her to this timely conclusion an hour later:

“Edmund’s deep piety and extreme asceticism would not be popular in our modern age, but his qualities of modesty, selflessness and generosity are worth emulating,” said Gunn, “while his rejection of self-promotion in favor of dedication to duty is a quality I think we would all like to see in our public figures and leaders.”

Gunn, who has a PhD in medieval literature, works in the area of English vernacular theology. She has written on Saint Edmund of Abingdon’s contribution to the development of vernacular theology in England.

Many of the resident campus Edmundites, religious studies faculty, campus ministers and other faculty joined undergraduates and members of the wider public in Tuesday’s audience for the 4:30 p.m. presentation. Sponsoring the event was The Edmundite Center for Faith and Culture, in what the Center’s director Fr. David Theroux, S.S.E. ’70 said was the first of several planned Center talks this year.

Fr. David Theroux, S.S.E. ’70

Fr. Theroux introduced the speaker, noting that Cate Gunn graduated from Southampton University in 2004 with a PhD in medieval literature; her thesis was on the early 13th century English guide for anchoresses, Ancrene Wisse. She taught in continuing education for many years, and more recently in the Department of Literature, Film, and Theatre Studies at the University of Essex.

Gunn connected personally with her audience right off by sharing that she lives close by to the town of Colchester in Essex, England, and so felt right at home in another Colchester.

Her opening tale relating the circumstances of St. Edmund of Abingdon’s birth was an attention-grabber. The saint’s mother was on a pilgrimage to the shrine for another famous medieval Edmund, a virtuous king and martyr beheaded by invading Danes, when she first felt Edmund kick in the womb as the story goes. That is why “Edmund King and Martyr is part of the story of Edmund of Abingdon,” she said, relating the connection she saw noted on the Society of St. Edmund website.

Gunn explained the “yawning chasm between history and hagiography” that these cases dramatize, relating legends with historical connections, replete with beheadings, splattered brains, a seemingly magical guard wolf of a talking disembodied head, and other tales of varying probable full historical veracity, but each more interesting than the previous.

In her stories of the Edmunds she wove in Thomas Becket, famous of the play “Murder in the Cathedral,” and noted that Edmund of Abington “spoke truth to power” between Becket and Richard of Chichester. One of her more interesting digressions was to tell of the often-misunderstood details surrounding Becket’s actual murder in the cathedral, and she noted ‘the best saints get beheaded, it fascinates me. She tied such martyrs’ deaths to the story of Sir Gawain and the green knight.

Terryl Kinder

Interestingly, the bodies of both St. Edmund the Martyr and Edmund of Abingdon were found to be incorrupt when their tombs were open within about 50 years of one another, Gunn related. She spoke of the Edmund’s close association with the Abbey at Pontigny in France, so important in Saint Michael’s Edmundites’ history relating to their founding in France in the mid-1800s with special devotion to St. Edmund of Abington. In Tuesday’s audience was Professor Terryl Kinder, visiting distinguished professor of art history, who lives beside Pontigny Abbey in France and is a leading authority on its history, and is teaching at Saint Michael’s this semester, as for many past years.

A life of virtue

St. Edmund of Abington

Gunn told in some detail how Edmund lived a life of “continuous, uninterrupted virtue” — as canonization in those times seemed to require. “The requirement for such a virtuous life of piety and asceticism points to the paradox at the heart of the medieval church: it was a powerful, hierarchical structure, but renouncing power could be a source of spiritual prestige and a different kind of power,” she said. The speaker related an account of a miracle that had St. Edmund levitating above the ground while praying on bent knees. She spoke of the importance of living a religious life in a monastery to St. Edmund.

She also spent some time describing the important work, Speculum Religiosorum or “The Mirror,” a most famous work of spiritual devotion attributed to St. Edmund and commissioned by a contemporary John Pery. Gunn said it appeared primarily a work written for the understanding and devotions of common people – men and women — and has a personal feel to it, which she illustrated with some passages on her accompanying PowerPoint presentation. This allowed her to bring clarity medieval writing texts that she projected and went word by word with a pointer to make it understandable to the audience.

Of Edmund speaking to us through The Mirror, she said this: ”When we talk of going to see ‘Shakespeare” we mean we are going to see one of his plays….by a process of metonymy the writer is identified with the writing. If we consider Edmund, not as the man, saintly though he undoubtedly was, but through the work by which he is known today and through which he was widely known in the later Middle Ages we can understand him as presenting a model of life and living: humble and pious, observing self-discipline while reaching towards transcendence. A saintly life, but one which could be accessible to lay people living in the world.”

She said near her conclusion that Edmund (and the commissioner Pery) through The Mirror, speak to us in the present and those in the future. Edmund or Pery “may never have been able to envisage readers in the 21st century, but we would do well to remember the advice at the beginning of The Mirror, as the blessed Bernard says and as here is put so simply: “To live perfectly … is to live honorably, lovingly and meekly.”

Cate Gunn delivers Tuesday’s St. Edmund Lecture.