Faculty historians set stage for coming spring play with suffrage stories

Panel part of Humanities Center spring series as Dean Galbraith joins Professors Garrett and Purcell for well-received presentations on women's voting rights activists

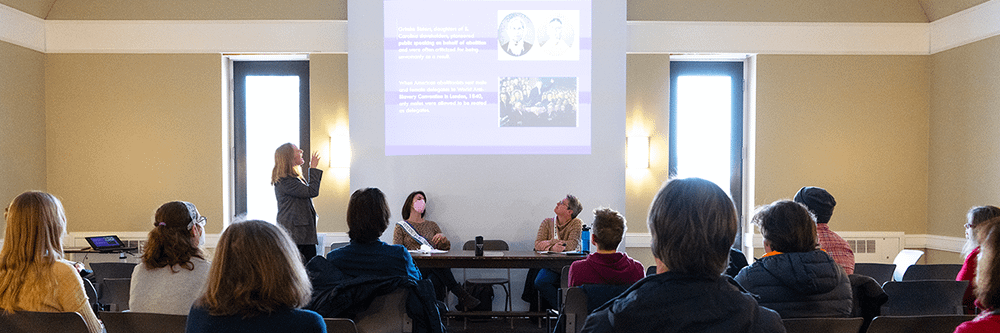

Panelists, from left, Alexandra Garrett, Dean Gretchen Galbraith and Jennifer Purcell, all of the history faculty. The large image behind the above headline shows Peter Harrigan introducing the panel. (photos by Patrick Bohan)

The upcoming spring dramatic presentation at Saint Michael’s about the struggle for women’s suffrage in the U.S. and the U.K. reminds us that people’s rights do not advance automatically or evenly without frequent expectable setbacks, a panel of faculty historians said Thursday evening.

“Just because you think you have rights doesn’t mean they don’t get taken away, so you constantly have to stand on those rights or they will be diminished,” said Professor Jennifer Purcell. She joined fellow British history expert, Dean Gretchen Galbraith, and early American historian Alexandra Garrett for the panel called “The Right to Vote: Women’s Suffrage in the UK and U.S.,” on March 9 at 4 p.m. in the St. Edmund’s Hall Farrell Room.

Introducing the panelists was Fine Arts/Theatre Professor Peter Harrigan, director of “Woman This & Woman That: An Evening of Suffrage Plays,” running March 22-24 at 7 p.m. each night in the McCarthy Arts Center Theater. The show includes two one-act plays and a suffrage poem set to new music by local musician and composer Tom Cleary.

These segments revisit a time when women’s advocacy and determination were catalysts to necessary social change: the right to vote, according to Harrigan. He explained how present issues inspired his choice along with the reality that mostly women audition for theater productions, so he wanted a show with abundant female roles.

Absorbing specific examples from history, shared with engaging flair by the historian panelists using PowerPoint slides, offered useful context for anybody planning to attend the play or simply seeking to be a more informed citizen. The panel was one among several spring presentations through the College’s Humanities Center.

Lending vivid immediacy to their historical accounts (and thanks to the veteran costumer/director Harrigan for providing them), the panelists all donned slogan-bearing sashes that cast members will wear in the play, much as early suffrage activists typically would for marches.

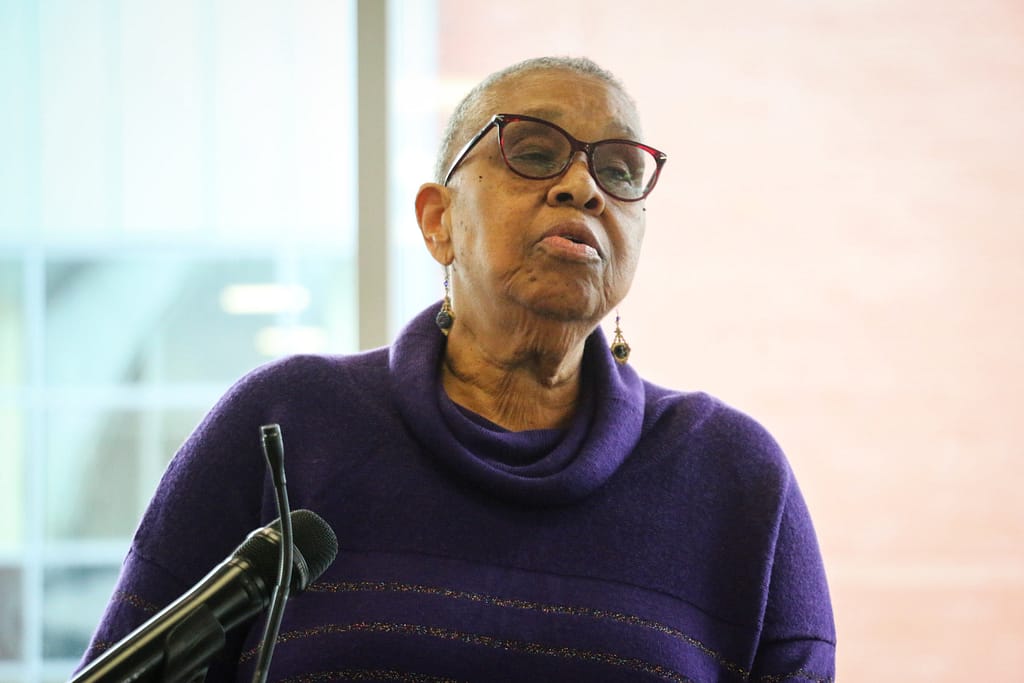

History Professor Alexandra Garrett is animated making a point during her talk.

Professor Garrett presented first, describing the colonial background for where our idea of voting comes from. A map helped her show traditions from early colonial powers England, Netherlands, Spain and France, with the English ideas prevailing. The British way of thinking about who gets to vote is based on the land – France was most interested in trade and to a degree making converts, the Dutch were mostly about trade, and Spain was mainly out for “gold and converts,” she said. Native Americans had a different idea of land “ownership,” causing problems.

With England prevailing in the colonies, voting rights and land equaled power, and land was fundamental to being an independent person, she said. She spoke of strong social notions in England and the colonies that women become ugly, loose women and bad mothers when they get political. She examined the U.S. Constitution language on voting, including an old draft that DID include women as part of the new political body, but later edits made that less explicit. She explained an idea of “Republican Motherhood” – women raise children to be good citizens and that is their political role. She described how gradually property requirements for voting dropped off before the Civil War, and more than 90 percent of adult white men in the U.S. could vote by 1840. She said most women were not fighting it in those times, with backlash re-surging about women being political at all.

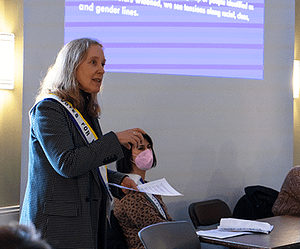

Dean Gretchen Galbraith presents.

Dean Galbraith said that suffrage is never in a vacuum. She spoke of the fight to abolish slavery as an example where “women learn to find voices and take risks.” She told the stories of some of those risk-takers, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls, NY, in 1848. Galbraith also spoke of Black women’s groups that arose for activism, noting, as the other speakers did, that some racism arose even within the women’s suffrage movement. She described currents in England to recognize non-landowners in England such as unskilled laborers with voting rights as being influential. The term “suffragette” emerges in the early 1900s she said based on a notion of “doing it right” among the women activists.

Professor Purcell went next. She described some voting rights legacies from Europe first to show how uneven was this development. (Swiss women finally got the vote in 1971!). She played devil’s advocate in laying out what opponents to women’s suffrage would say in the early 1900s at the time of the plays’ action, then went into the case in favor of giving women the vote from that era.

Professor Purcell stresses a point during her presentation.

She told of a British lord who said women should not have the vote since they do not fight wars and die for their country. She showed early propaganda against the vote for women with her slides. She told of the Women’s Social and Political Union, of women getting involved in tax resistance (it did not work since the government can come after you), then massive marches. She and Galbraith also described local-level activism, noting it went much farther than the most public major demonstrations.

In a question period, one questioner among the more than 40 audience members of students, faculty staff and the public shared some specifics of women’s suffrage activism in Vermont in history.

Garrett said for her a key point of all this is that “in American history particularly, there is not an upward trajectory of progressivism, but rather backlash all the time, with one step forward and two steps back” right up until women achieving the vote in 1920, and in some ways even into modern times.

Audience members seemed absorbed by the panelists.