Summer research spotlight: Kayne Wentzheimer and Marissa Miles

St. Mike's students join ongoing work of Professor Ruth Fabian-Fine with spiders to learn more about auditory neural systems in humans, possibly enabling medical advances

Marissa Miles ’22

Since coming to Saint Michael’s College, Marissa Miles, a rising senior from Colchester, VT, has wanted to participate in Professor Ruth Fabian-Fine’s research on the Central American Wandering Spider

During Miles’ senior year of high school in Colchester not far from campus, Fabian-Fine of the biology and neuroscience faculty allowed her to intern and accompany the professor in her research since Miles needed hours for her high school AP biology course.

“The way she talks about the spiders and how they help represent us (humans) in the research was very interesting,” said Miles. Now, in the summer of 2021, Fabian-Fine serves as a mentor for multiple students, including Miles, on their journey through their research topics regarding the spiders.

Along with Miles, rising senior Kayne Wentzheimer from Lisbon, ME, is another student working Fabian-Fine’s spider research group. He said he reached out to Professor Fabian-Fine asking about summer research, “and although she has been working on this research for nearly two decades, it is a collaboration between all of the students and Ruth to find some results this summer [that tell us even more about these spiders].”

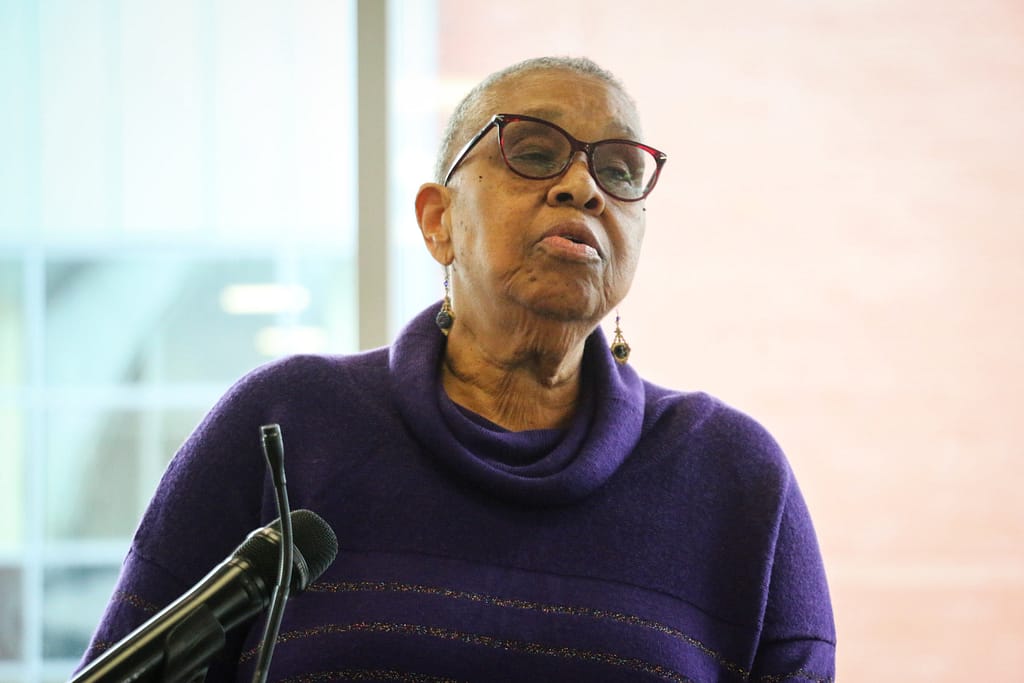

Professor Fabian-Fine and a spider in her lab.

While all the students are collaborating in the research, some are focused on certain aspects that differ from the others.

“I am looking at the synaptic innervation patterns of the leg muscles in the Central American Wandering spiders,” said Miles, “I will be looking at the neuronal synapses (the meeting point) that the different motor neurons have on both sensory neurons and the muscles themselves. I am looking at what neurotransmitters are released and their effect on these areas.”

Even though Miles’ research differs from Wentzheimer’s research on the spider’s auditory system, they can collaborate because the spider’s auditory system is located in its legs. “The main goal of this project is to find out how sensory systems are modulated and influenced by our brain,” said Fabian-Fine. “It is similar to what people do when they eavesdrop on another conversation.”

Kayne Wentzheimer

Wentzheimer used an example that further explains this process: “If you focus on someone talking, you may still hear the air conditioning in the background. However, if you focus on the air conditioning, your brain can tune out the sound of someone talking [in order to make the air conditioning seem louder]. So, while eavesdropping, our brains are able to tune out all other sounds to focus on what the other people are saying.”

However, this is difficult to study in humans, Fabian Fine said, explaining that the human ear is encased by bone, which includes the skull and the cochlea. However, spiders have the same system, according to the professor, and since their auditory system is in their legs, it is easier to dissect. This allows easy access to investigate, look for transmitters, and the different neurons that come from the brain.

As with humans and eavesdropping, when the spiders hunt and see their prey, they are able to stop and listen. Their brains modulate their sensory neurons to focus on the sound of the prey. “This is what we are focusing on,” said Fabian-Fine — “what connectivity is made? Where does this connectivity come from? What kind of biochemical substances are being released onto these sensory neurons in order to make them more or less alert?”

Fabian-Fine, Wentzheimer, Miles, and others are studying those questions to find what kind of biological molecules are released onto the sensory neurons to make them more or less sensitive, since that sensitivity is what allows a spider – and by correlation, a human — to hear more or less; thus, discovering how those sensory neurons actually respond to stimuli in the research “helps us learn more about the human auditory system,” said Miles.

So, why is this research important? “Medical advances,” said Wentzheimer. Professor Fabian-Fine shed light on why this research may result in medical advances: “Mental disorders are believed to be an imbalance of the transmitters within the neurons of the brain. So, in order to find out if there’s an imbalance of transmitters within auditory conditions that patients have, we need to identify those transmitters,” she said.

In the end, the goal is to describe how the auditory neural system works in order to treat patients. This allows for the transfer of those models in the spiders to the mammalian (human) system, to see if the components are the same.