Personal connections put human face on history research for dissertation

Edmundite Fellow Jolivette Anderson-Douoning shares absorbing story of her grandmother in post-WWII Louisiana, with lessons about race, rights, labor, faith and possibility

Jolivette Anderson-Douoning emphasizes a point during Tuesday’s presentation from her dissertation in the McCarthy Recital Hall with a PowerPoint title slide behind her. (Photos by Elizabeth Murray ’13)

“Putting a real woman’s face on valuable history” is how an Edmundite priest in the audience during questions and answers summed up a well-received presentation of dissertation research by Jolivette Anderson-Douoning Tuesday evening in the McCarthy Arts Center Recital Hall.

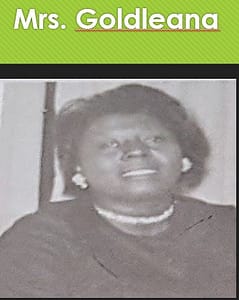

His observation was literally true: The speaker placed an image of her late grandmother, “Mrs. Goldleana,” (below left) on every PowerPoint slide appearing behind her as she brought the audience of nearly 50 (plus many more on Zoom) along through a deeply personal family story from post-war Louisiana. It was an absorbing tale that illustrated and humanized important themes of American history, from racial hate, segregation, labor economics and civil rights struggles to faith, survival, perseverance and possibility.

A distinguishing quality of the talk, other post-talk commenters further observed, was how Anderson-Douoning interwove love, personal connection and passion through meaningful academic research. The presenter is the Edmundite African American Fellow in the Saint Michael’s History Department and a PhD Candidate in the Purdue University American Studies program.

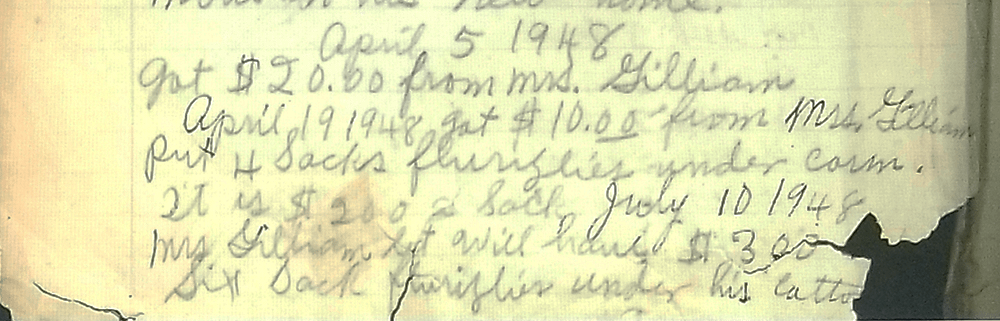

At the heart of her research is a ledger documenting the everyday activities of Mrs. Goldleana Harris Mosley Abraham, a Black woman living in a segregated neighborhood of Shreveport, Louisiana, after World War II, providing historical insight into the limited labor opportunities and racist practices Black workers had to overcome in that period.

Anderson-Douoning described how she used the ledger kept by her grandmother to inform part of her dissertation research. The North Louisiana native and former Jackson, Mississippi, scholar titled her public lecture “The Hands that Picked the Cotton: A Black Woman’s Labor as Acts of Liberation in Segregated Shreveport,” based mostly on her dissertation chapter, “The Work (Labor) House,” during the free event on campus.

According to Anderson-Douoning’s research, the lived experiences of her grandmother are inextricably linked to the cotton and timber industries in Caddo Parish and believed to be interconnected with labor organizing work done by everyday people in Shreveport. She sees Mrs. Goldleana’s different jobs – picking cotton, working in the chair factory, serving as a seamstress, and canning foods – as acts of freedom, not enslavement, because she did those things by choice. She also put to use the skills that she brought with her when she migrated to Shreveport from rural Louisiana.

The lecture focused on a period after World War II leading into the Civil Rights activity of the 1960s in Shreveport, which connected to other Civil Rights organizing in other areas of the Deep South. At the time, Louisiana state laws required Black residents to live in “All Black” or “Colored Only” neighborhoods. Mrs. Goldleana lived in the Hollywood neighborhood, where the speaker grew up just down the street, visiting her grandmother often.

In introducing Tuesday’s talk, the speaker’s History Department colleague and Chair Professor Jennifer Purcell welcomed a mix of students, faculty, staff and community members gathered in the hall. Also joining, she said, was a large audience viewing the lecture via Zoom, from other locations “far and wide.” She thanked the mayor of Shreveport for publicizing information about the talk.

The speaker was animated and passionate in her presentation.

To start, Anderson-Douoning honored elders in the audience as is her tradition, particularly thanking Margaret Bass, formerly of the College faculty/staff, and the speaker’s history faculty mentor from last year, Kathryn Dungy – saying that while both are no longer at Saint Michael’s, “the work and energy they brought here are still present today.” She specially mentioned her daughter Nadja (also present), “my heart, my soul, my purpose” as “the sixth generation from a lineage of black women who lived and worked in North Louisiana.”

The religious and service roots of Saint Michael’s and its Edmundite founders were prominent through the talk. The speaker spoke about the duty we all have to counter hate – “a byproduct of evil that shows up in our everyday lives in the form of ignorance [and] the absence of freedom.” She said Edmundite work through history in their southern missions and elsewhere, has combated that hate directly.

Anderson-Douoning spoke unabashedly of faith in Jesus as central to the story of her grandmother — something handed down to her, and, in her view, inextricable from the history and mission of Saint Michael’s too, even while the College community properly embraces and welcomes into the community other belief or nonbelief backgrounds as part of that faith.

She quoted the Apostle Paul early in the talk, and his words from Corinthians, that “every day I am in danger of death,” noting how those words literally applied to Black people in the segregated South during her grandmother’s life, helping explain gospel resonance in her grandmother’s community and the central role of church. Church also was a community center for her family and neighbors, and, likely — though she still is seeking more evidence in research — a site for labor organizing, under the radar of those who might oppose it.

Beyond the apostle, the speaker shared powerful language on the racial, societal and constitutional issues that ultimately affected her grandmother and Black Americans, from such diverse sources as the great Black orator and leader of history, Frederick Douglass, to the present-day historian Heather Cox Richardson. Their citations described the harmful and false stereotypes about Black people and their labor so common through history even to the present day. Yet, the speaker asserted, her grandmother’s well-documented lived experience – her choice to use her labor to assert her freedom and fight back– was an eloquent counterargument to those ugly prevailing views from history.

Anderson-Douoning said beyond strong religious faith, her grandmother held “A deep belief in the practice of liberation, being free to make her life what she wanted to be.” The speaker invited the entire audience to read along with her the words of the preamble to the U.S. Constitution. She said it is a duty for those studying and teaching today at a College such as Saint Michael’s to ask questions as part of valuable academic inquiry with a moral compass, about why those harmful stereotypes and fears persist even today.

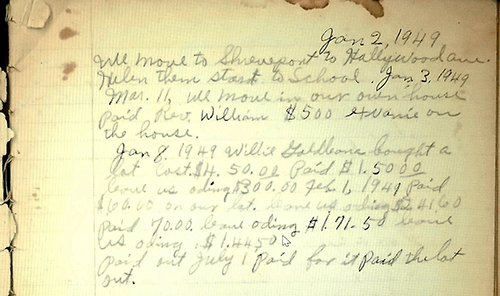

An entry from the ledger kept by her grandmother tells of moving to a new home in Shreveport’s Hollywood neighborhood.

The speaker showed how everyday details of her grandmother’s life from her ledger gave a vivid view of life and society in those times. Beyond those insights, however, the ledger provides a humanizing glimpse of other aspects of life, from schooling and children, to leisure such as learning to play piano – the speaker’s mother was a church choir pianist from the age of 15. Anderson-Douoning wound up the presentation quoting the late Edmundite Father Maurice Ouelett, an active civil rights leader in the Selma missions in the 1960s, from his master’s thesis, affirming that ‘segregation cannot be tolerated in light of Christ’s teachings.”

A post-talk question session was animated and interesting. A woman asked the speaker to talk more about her grandmother’s “joy and love in her life,” and in response, Anderson-Douoning sang some lines from a favorite song her grandma would sing about a shining light. She told of Mrs. Goldleana’s love of a good joke. A student in the audience later asked what she found to be “most profound about her that you didn’t get to say?” The speaker had a one-word initial response “Survival.” Then she elaborated, saying, “I know all of us need what my grandmother had in her to keep her moving and keep her going in the midst of it.” She said she was not sure she personally had the stuff to turn the other cheek in such situations rather than fight back, and so might not have survived similarly through the challenges of that period.

Jeffrey Trumbower, vice president for academic affairs, was curious about economic opportunities for Black people in those times given that banks were not typically a realistic option. Anderson-Douoning said mostly it was the neighborhood that rallied to help one another with loans and savings, or hiding savings under a mattress. Billie Miles ’76, now retired longtime Saint Michael’s IT employee, said that far beyond just surviving, Mrs. Goldleana’s journal documented “thriving,” adding, “It’s a life of possibility and manifestation.”

Nat Lew of the Fine Arts faculty closed questions on a similarly positive note. “Coming at this as an academic, so much of what we do too often seems dry and academic,” Lew said, “but this is a labor of love – to see you putting that love together with intensely deep scholarship is very motivating to me. We need to remember to be like you and bring our passion and our deep personal lives into what we do as scholars since too often that is lost.”

Another ledger entry, this from 1948, documents daily life during spring planting and associated expenses.