Natural Area plays predictable, useful role during epic Vermont flooding

Biology Professor McCabe explains why wetlands that resulted from key federal easement are far preferable to the former farm fields, for many reasons

The wide photo behind the headline above shows the top part of the same view before flooding, while here is the full “path” leading to the spot as waters rose. (Photo Declan McCabe)

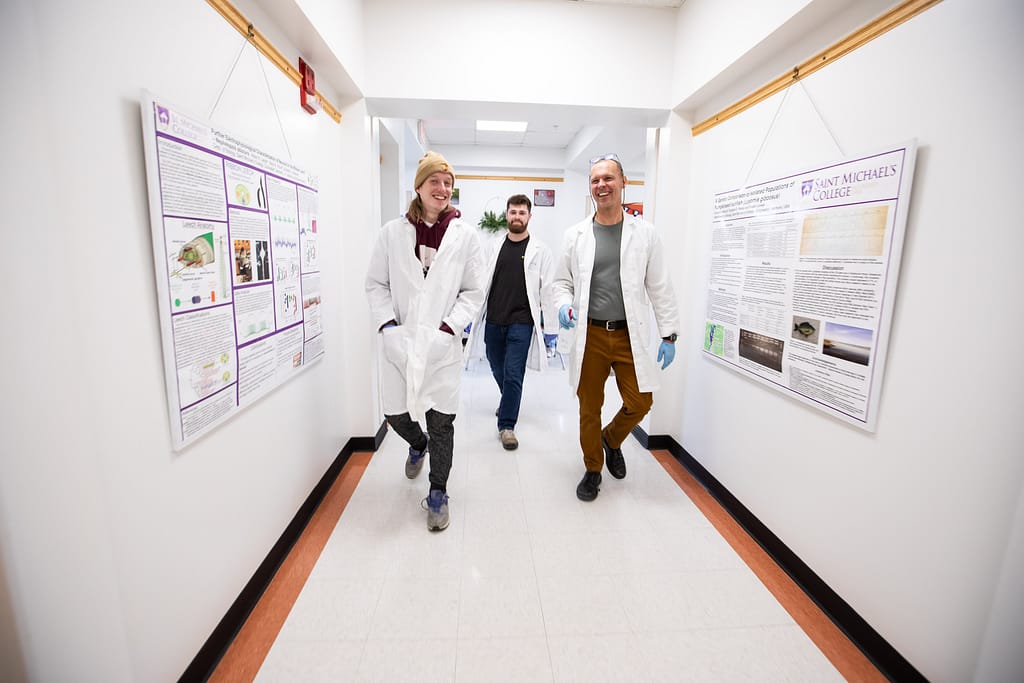

In the few hours between biology Professor Declan McCabe’s noon and 3 p.m. visits Monday to the Saint Michael’s College 365-acre Natural Area on a flood plain along the Winooski River across Route 15 from main campus, a walking path became a virtual waterway.

Yet McCabe, the Natural Area’s chief faculty steward, said such predictable and manageable rising water there amid historic and devastating statewide flooding in Vermont of recent days testifies to the wisdom of the federal conservation easement for the College that turned former agricultural fields along the river into the now well-used and attended tract for education and recreation.

“There’s a little creek that goes across one of our trails and we know water is going to come up that creek backwards, so the water will rise — but not like you see on the news where houses are getting carried away,” McCabe said. “Still, it’s kind of spectacular to be down there and see the flood line rising as little worm holes are filling up and giving up air and everything is sort of percolating.”

He explained how turbid and brown water from the Winooski River backing into the Natural Area wetlands through that creek “will cover every stem and leaf with a silt as the water goes down, and that’s really good, since that’s soil loaded with phosphorous that doesn’t go into Lake Champlain — so our wetlands are naturally filtering the water.”

McCabe vividly described how the ancient Winooski River predates and therefore “cuts through the Green Mountains like a knife from Montpelier” providing the path through those mountains that humans use for highways and train tracks, farms and towns.

Declan McCabe

All along the way, the river is collecting a lot water fed by many feeder streams, with runoff coming from farm fields containing fertilizer phosphorous or even natural phosphorous from the wilds. Phosphorous is good for plants and nature in moderation, but is bad once it reaches Lake Champlain since it contributes substantially to toxic algae blooms that have become such a problem.

From his office computer in Cheray Science Hall or even with his cellphone, McCabe regularly checks an online gauge at the dam along the Winooski River in Essex by Route 2A. He said it showed a peak last week before the recent rains of 4.5 feet, but by Monday afternoon it was rising steeply toward 9 feet, with flood stage officially at 12 feet. By early Tuesday, it had neared the predicted 20 feet with a chance to go higher before an expected Tuesday afternoon crest.

“It comes right on up to our trails,” said McCabe, who uses data from the Essex dam gauge for his aquatic biology course. “It’s a typical, textbook hydrograph doing exactly what you’d predict,” he said of the river rising and receding with attendant flooding. “With spring melt it’s going to flood most years, but the question is, how many times? If we didn’t have those wetlands, the flooding downstream could be more devastating. They capture a lot of water.”

He gave the example of Hurricane Irene in 2011 and a dramatic difference during that event between flooding in Rutland and Middlebury. Otter Creek in Rutland became “channelized” and as result experienced bad flooding then, while Middlebury, downstream at an even larger point of Otter Creek, had less damage, primarily since “they have extensive wetlands in Addison County.”

A trail marker before the flooding….

When the Saint Michael’s riverside land was a farm before the Natural Area – up until about 2018 – “It would have been a very, very different story” in such flooding, he said, with the river flowing fast over land and washing phosphorous downstream rather than filtering it as it does now.

McCabe has viewed aerial photos from previous decades along with studies that indicated a “tipping point in the 1990s because of climate change” in this region. Many more storms started coming up the east coast, bringing far more rain to the Northeast. “There were areas you could have farmed in the ‘60s and ‘70s that you couldn’t possibly farm in the 1990s or 2000s,” he said.

Since every plant needs phosphorus, a program in the 1970s paid Vermonters to put it down on fields and “now we have legacy phosphorus in the agricultural basins in Vermont,” he said, “It is devilishly hard to reduce the flow to the lake” as a consequence. Cattle in feed lots are another phosphorus creator, since manure is rich with it too.

The biologist said that ironically, the recent floods might actually cut short Lake Champlain beach closings this summer since lake temperature and stratification are other variables leading to algae blooms and the flood waters should ease those stressors.

…. and the same spot after.

None of this is anything really new to McCabe, who once in recent years went down to the Natural Area during lesser flooding wearing waders to retrieve trail cameras he uses with students. However, no cameras are out this summer, even though several summer research students are doing work in the Area, studying patches of old-growth forest to make comparisons with newer growth areas.

He said a recently constructed outdoor classroom pavilion that is down in the Natural Area remains “high and dry” by deliberate forethought in the permitting and planning for its location. In fact, Katy Farber of the College’s graduate education faculty had some of her Master’s in Teaching students doing a project with nets and buckets just before the recent rains, with excellent results.

Katy Farber’s education class this weekend, pre-flooding, in the Natural Area.

As to the plentiful animals that live in the Natural Area, McCabe said, “if you get off the trails you find deer beds – flattened vegetation, and they’ll get pushed up the hill by the rising flood.” Coyotes and bobcats also get pushed up and floods provide an opportunity to “catch rodents on the run from the rising water,” he said. Just recently he saw a “freshly fledged woodpecker’s mom dive-bombing a weasel.” Once the water recedes after flooding, volunteer friends of the Natural Area typically will help with cleanup, given that items like buckets, bait containers and bags invariably will wash down.

McCabe said he likes to watch the trail marker posts along the Area’s trails to see how high the high-water mark might go on those seven-foot four-by four posts. “Much of the Natural Area is in floodplain and 2 of the 4 miles of trail were submerged as of Tuesday, July 11,” he said. “Floods are expected processes and the Natural Area will recover!” He advised people to stay off flooded trail since murky flood waters hide tripping hazards and may contain bacterial contamination. Staying off the trails also reduces needless erosion, he said. “Once this emergency passes, I hope folks will consider helping with cleanup. Gloves and trash bags will be left at the trail head next week – toss branches and natural debris off trail to facilitate mowing. Please bag up buckets, coolers, and flood-borne flotsam and drop at the compost area.”

Wetter than usual wetlands in the Natural Area late Monday. (photo Declan McCabe)